Introducing a Regular Column

About Migratory Fish in the Watershed

The Connecticut River hosts many spectacular migrations. You can witness the fall spectacle of swallows, the comings and goings of osprey and eagles, the annual invasion of warblers, and even the southward passage of monarch butterflies. However, some of the most historical and ecologically-significant migrations of the Connecticut River are missed by most. These are the annual migrations of fish—specifically diadromous fish. These are a handful of specialized species that move between freshwater and saltwater for the purpose of spawning. Our River has been well-known for such migratory runs of fish from prehistoric times to the present time. Their presence has made an impact on the history of the region, indeed, the nation, and has been a factor for the many designations the River has had bestowed upon it including as a Wetland of International Importance under the Ramsar Convention. If you were on the river in a boat during the springtime, nothing would alert you to the fact that there were hundreds of thousands of migratory fish of more than a dozen species passing underneath you.

The 410-mile long Connecticut River once supported the largest Atlantic Salmon run in the US and the longest migration of the species in North America. Samuel Peters wrote in the 18th century: “The salmon, large and small, are exported both pickled and dried,” attesting to the abundance being significant enough to allow export. The American Shad, the state fish of Connecticut, helped sustain George Washington’s troops at Valley Forge. River herring were salted by the barrels and sent to the Caribbean in exchange for molasses and rum. At one time in the young life of the Colonies, sturgeon shipped out of Middletown was the leading colonial export. The River still may support the largest documented run of Sea Lamprey on the East Coast, and—perhaps more surprising—that is a good thing!

When young American Eels (elvers) reach a dam or waterfall, they may leave the water to find wetting passageways over the obstacle. Often specialized eel passes are required to help them along their journey. These fish are 4–5 inches long.

Photo courtesy of Sally Harold.

To be clear, we will not be writing a fishing column on how and where to catch fish. Our goal is to introduce readers to the marvelous and often overlooked world of our River’s migratory fish. Each species has its own story, which is woven around its biology and life history. The runs of the various species of fish combine to create a river almanac, generally predictable in the annual sequence of the fishes’ comings and goings but always with the potential for a few surprises each year. In the spring, as you bundle up against the early March snows, we’ll explore together the first run of glass eels arriving from the Sargasso Sea and, as the days grow longer, talk about the expected returns of osprey and Alewives. We’ll share news of the first arrival of Alewife to the Connecticut River at the Mary Steube Fishway in Old Lyme. We’ll write about the shadblows blooming and the American Shad running up the lower river, dodging the last few nets of a dwindling historical fishery, and we’ll bring you underwater where we witness the spectacle of spawning Blueback Herring, a species of Special Concern in Connecticut. We’ll follow the runs upriver, to fishways in Massachusetts and Vermont and go behind the scenes where biologists count the shad and other fish moving north, while downstream, the netters put away their nets for the season.

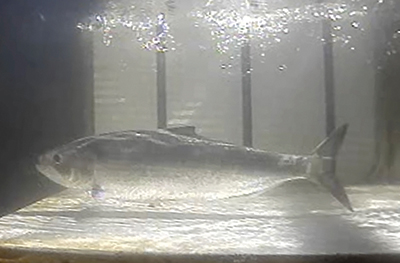

An American shad is captured by an underwater camera in the Moulson Pond Fishway on the Eightmile River in Lyme, CT. Building fishways allows American shad runs to expand out of the main river and ascend tributaries like the Eightmile River.

Photo courtesy of CT DEEP Fisheries Division.

We’ll also investigate the amazing elver run to inland dams and waterfalls. The same little eels that arrived at the mouth of the river in March are larger in June and scaling barriers to continue their upstream journey. We’ll be back underwater documenting that feat. We’ll invite you to accompany us on the annual Sea Lamprey Nest Survey when government biologists join forces with volunteers to count the nests of this fascinating fish species to help track its recovery in tributaries in all four states. While we count nests in Connecticut, biologists with the Green Mountain National Forest watch lampreys spawn in the White River in Vermont, over 260 miles from the ocean. We will explain to you why Vermont Fish and Wildlife can promote the restoration of Sea Lamprey to the Connecticut River drainage on the east side of the state while joining the effort to eradicate the same species from the Lake Champlain drainage on the west side of the state.

During the summer, we’ll be out on boats looking for leaping sturgeon—the Shortnose Sturgeon and the Atlantic Sturgeon, both of which are on the federal endangered species list. While some frolic in the tidal area, many are being lifted over the Holyoke Dam to make their way up to the Turners Falls spawning grounds. In the fall, oh, there is just too much to even mention it all here! But the fun just keeps coming.

The history of migratory fish is always intertwined with human history, both that of Native Americans and the European settlers that came later. As we slog upstream, we’ll show you waterfalls that stopped the runs naturally and dams that stopped the runs artificially, along with ruins of mills that made paper, ivory for keyboards, drill bits, cloth, and electricity. More than pollution or nets, it was these dams that reduced the runs of fish to a fraction of their former size. There are over 4,000 dams in the state of Connecticut alone, 477 of which are in the Connecticut River watershed. The watershed is estimated to have a total of 1,422 dams, distributed through all four states. We want to introduce to you the efforts being made by many to make the Connecticut River a better place for migratory fish and increase the numbers. From Old Lyme and Old Saybrook in Connecticut to the Northeast Kingdom of Vermont, dams are coming out. We’ll bring you along throughout the watershed to see some of these projects that are reconnecting habitat. Plan on joining us with each new issue of Estuary, won’t you?

Sally Harold, left, and Steve Gephard stand on the Norton Mill Dam on the Jeremy River in Colchester, CT, in 2016 right before it is demolished to open up miles of upstream fish spawning waters. Photo courtesy of Sally Harold.

There are countless fish stories to be told about the river. Stories about the fish, themselves, how the fish migrations synchronize with other migrations, the efforts to restore lost runs, and the people doing the work. It is those stories that we will be telling you in this recurring column in Estuary magazine. We are Steve Gephard and Sally Harold.

Steve has been working with migratory fish and fish habitat as a fisheries biologist for over 40 years and grew up on the river as a true river rat. He has recently retired from a long career with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP) where he supervised the Fisheries Division’s Diadromous Fish program and its Habitat Conservation and Enhancement program. He was in charge of the salmon restoration program for years and was the Department’s expert on fish passage (getting fish around dams). While he is now doing independent work as a consultant, he still holds a position with the DEEP, focusing on special projects.

Sally spent 18 years in the conservation trenches with the Connecticut Chapter of The Nature Conservancy and was its Director of River Restoration and Fish Passage. She was the project manager for many fish passage projects, including leading the charge on Connecticut River tributaries where she removed dams in the watersheds of the Salmon and Eightmile rivers and built three fishways on the Falls River and another on the Mattabesset River. Since childhood, she spent a lot of time on a Vermont tributary of the Connecticut River. Currently, she is an independent consultant working on fish passage projects. The two of us worked together on many projects and are excited to be collaborating on these quarterly articles for Estuary.