There’s a sailor superstition about changing a boat’s name. State of New York, largest and costliest steamer ever to run on the Connecticut River, was to be called Vermont. Few vessels had worse luck. State’s misfortunes began in 1871, when the 300-foot sidewheeler struck a large stone that had gotten away from workers building the Saybrook breakwater. (The principal run in those days was New York to Hartford through Long Island Sound.) Damage to her hull was minor, but State’s schedule was thrown off by a day. On her very next sailing, the steamer piled up on Pot Rock while negotiating Hell Gate. Over the next nine years, State of New York collided with a Brooklyn pier, a Norwich boat, and Joshua’s Rock just up from the mouth. But her worst accident was August 28, 1881, when the steamboat struck a hidden river snag off Salmon Cove, tearing a six-foot gash in her bottom. Harvey Brooks, the pilot on the steamer, wanted to run the boat onto the flats above Lord’s Island but could not prevail upon Captain Peter Dibble to do so. Dibble beached the big steamer quickly, driving her up on the west bank opposite Goodspeed Landing. This was also opposite the glittering Victorian Opera House, built a few years before by the steamboat magnate William Goodspeed.

The impresario tried to make the best of the situation, offering a twin bill of Uncle Tom’s Cabin and a tour of the wrecked steamer, but it wasn’t enough. In the end, the wreck of the State of New York forced Goodspeed’s Hartford and New York Transportation company into receivership, and the businessman himself died a year later from illness brought on by overwork.

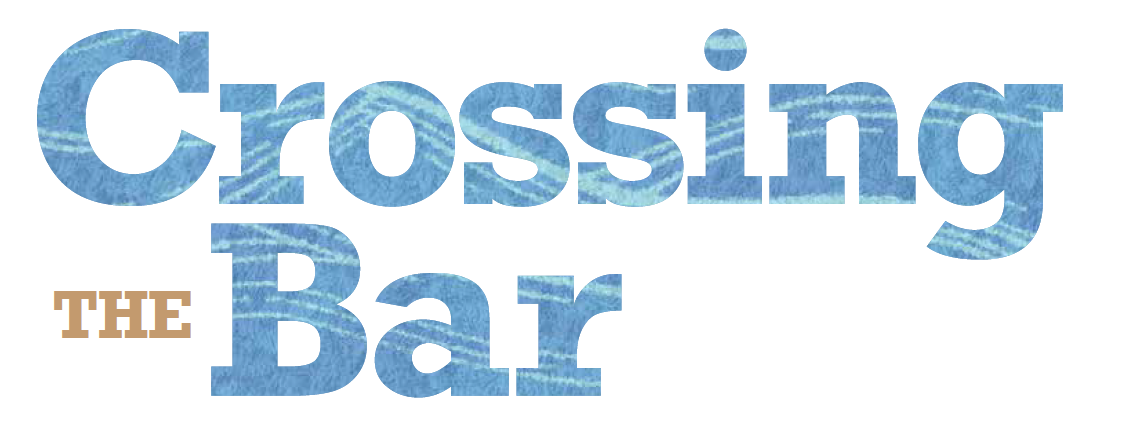

At 410 miles, the Connecticut River is New England’s longest waterway. Yet it is navigable for only 50 miles, from the wide river’s mouth at Saybrook to the now vanished State Street Landing at Hartford where the big side-wheelers used to tie up. For pilots in the heyday of steamboating, the trip upriver was fraught with danger. “It takes experience to pilot up the Connecticut River,” Captain William H. Hills, commander of the steamer Middletown once said. “You have to be alert, every minute. We used to get stuck on sandbars every now and then and there was nothing to do but wait until the tide rose. Fogs are a nuisance and a lot of trouble to a steamer. We were supposed to run on schedule and all the passengers wanting to know what time we’ll get to New York. If the fog grew too dense, we had to stop altogether, but usually we could keep going at a reduced speed. At that time, oil lanterns at the top of a stick were the only signals we had. Now, there are some towers with lights, but there still is improvement in the way of lighting up the river for boats.”

At 410 miles, the Connecticut River is New England’s longest waterway. Yet it is navigable for only 50 miles, from the wide river’s mouth at Saybrook to the now vanished State Street Landing at Hartford where the big side-wheelers used to tie up. For pilots in the heyday of steamboating, the trip upriver was fraught with danger. “It takes experience to pilot up the Connecticut River,” Captain William H. Hills, commander of the steamer Middletown once said. “You have to be alert, every minute. We used to get stuck on sandbars every now and then and there was nothing to do but wait until the tide rose. Fogs are a nuisance and a lot of trouble to a steamer. We were supposed to run on schedule and all the passengers wanting to know what time we’ll get to New York. If the fog grew too dense, we had to stop altogether, but usually we could keep going at a reduced speed. At that time, oil lanterns at the top of a stick were the only signals we had. Now, there are some towers with lights, but there still is improvement in the way of lighting up the river for boats.”

Meandering rivers like the Connecticut cut away their banks on one side and build them up on the other. The channel is constantly shifting. Boatmen had to learn to read the river and remember all the changes. They had to know it in sunlight as well as in starlight, in fog and blackness. They had to know that it appeared one way on the down trip, and another way on the up journey. “The river is deeper today and wider than it used to be, but still there are numerous sandbars and

Meandering rivers like the Connecticut cut away their banks on one side and build them up on the other. The channel is constantly shifting. Boatmen had to learn to read the river and remember all the changes. They had to know it in sunlight as well as in starlight, in fog and blackness. They had to know that it appeared one way on the down trip, and another way on the up journey. “The river is deeper today and wider than it used to be, but still there are numerous sandbars and

shoal waters,” Hills said. “The Connecticut is seldom what you call normal. Fog or ice or high water or low water, and the channel keeps changing. Freshets change the channels. And here and there are fish piers that once were built of stone for the use of fishermen and nobody took them away. They’re not used anymore, and some got knocked down by ice, but you have to know where they are.”

The first European to navigate the Connecticut was the Dutchman Adriaen Block, who sailed up the waterway Native Americans called Quinatucquet, or “Long Tidal River,” in the spring of 1614. Block, for whom Block Island is named, had been gathering beaver skins on the Hudson when clashes with a rival Dutch fur company culminated in the burning of his ship Tyger. The resolute skipper built a new ship with timbers salvaged from the Tyger, a 44½-foot sloop he christened Onrust, roughly translated as “Trouble” or “Strife.” Piloting the vessel through the whirlpool currents of Hell Gate, Block sailed eastward along the coast of Long Island Sound, where he came upon the Housatonic River, which he called “River of Red Hills,” from the iron-stained basalt ridges in the distance. The wide Connecticut he named Versche, or Freshwater River, in contrast to the brackish Hudson. Block explored the Connecticut as far up as present-day Hartford, and a little beyond. As if to confirm his success at fur trading, the town of Windsor claims Block established a fur trading post there.

Onrust was a beamy, shallow-draft vessel, and Block slipped easily over the treacherous sandbar at the mouth of the river and the shoals above Middletown—hazards steamboat pilots would later know as Quarry Bar, Pistol Point shoals, Dividend Bar, Log Bar, Wethersfield Bar, the Clay Banks, and Hartford Bar. It was tricky sailing, to be sure, negotiating all the twists and turns against a headwind, but Block made his way as far as Enfield before the falls turned him back. In his log the navigator wrote: “The depth of water varies from eight to twelve feet, is sometimes four and five fathoms [24–30 feet], but mostly eight and nine feet. The river is not navigable with yachts for more than two leagues farther, as it is very shallow and has a rocky bottom.…This river has always a downward current so that no assistance is derived from it in going up, but a favorable wind is necessary."

Not long ago, a 40-foot sloop heading up the river to Portland grounded on a sandbar off Haddam, and a diver in scuba gear was sent down to work her free. In the age of sail, there was kedging—sending out some sturdy young lads out in a longboat with a ship’s anchor, which they ran out as far as they could before dropping it overboard. Then it was back on deck, hauling on the capstan and inching toward the deeper water, the chore relieved somewhat by a hearty capstan chanty:

Windy weather boys, stormy weather, boys

When the wind blows we’re all together, boys

Blow ye winds westerly, blow ye winds, blow

Jolly sou’wester, boys, steady she goes.

Steamboats need a deeper channel than sailboats. In many places above Middletown five and a half feet was the only depth that could be counted on safely. There was talk of improving the channel as early as the 1650s, but nothing much was done until the churning vessels came along in the early 19th century. In 1806, a ten-feet channel was dug between Middletown and Hartford, and a company granted rights to collect tolls for sixty years for this and other improvements.

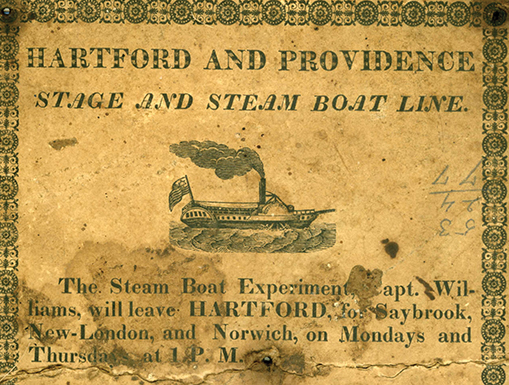

The Experiment, first passenger steamboat on the Connecticut River, steamboat sign, 1824.

That was before Robert Fulton, the supposed inventor of the steamboat, chuffed up the Hudson in the Clermont, but Hartford folks had already witnessed Captain Samuel Morey (in 1791 or thereabouts) churn past the wharves in a steamboat of his own devising. Morey piloted his little stern-driven craft all the way to New York, the first long distance trip in a steamboat. However, because of the Fulton-Livingston monopoly, regular steamboat service between Hartford and New York did not begin until 1824 when the 127-foot sidewheeler Oliver Ellsworth, commanded by Daniel Havens of Norwich, “a gentleman of experience in the carrying of passengers and navigating the Sound,” splashed up the River in the spring of that year. A year later a slightly larger vessel was placed on the route, Macdonough, named for a Naval hero of the War of 1812, Commodore Thomas Macdonough, who had died recently and was buried at Middletown. In those days, steamboats also carried sails to help the steam.

From those crude beginnings evolved the Hartford and New York Steamboat Company, which maintained three palatial sidewheelers, City of Hartford, Granite State, and the largest, State of New York. The three boats maintained daily service between Hartford and New York, leaving both ends of the line at four o’clock in the afternoon—the Hartford boat docking at Pier 24 on the East River, Peck’s Slip, at about 5 a.m., and the boat which left New York churning up to the State Street Landing in Hartford at about seven in the morning—provided always the boat was not delayed by fog or grounding. In that case, William Goodspeed, manager of the line, would step out onto a balcony of the Opera House overlooking the river and swear at his captains for arriving at the dock at 8 a.m. instead of 3 a.m. as they should have done normally.

These big sidewheelers were difficult to navigate in the torturous reaches from Saybrook to Hartford. Four men were needed to swing the heavy rudders. Beacons or lights were few and far between in the old days, and a pilot had to know the reaches blindfolded. With the exception of Lynde Point Lighthouse, erected in 1839 to mark the entrance to the Connecticut River, a program of navigational aids was not established until 1856, when three lights were built on the river—one on Calves Island off Lyme, another at Brockway Reach in Joshuatown, and a flashing light on Devil’s Wharf in Deep River. The first leading lights or range lights, which when aligned provide a bearing, was placed at Divided Bar in 1889, and by 1953, there were twenty separate range light installations from Saybrook to Hartford, practically one at every corner.

“Today, you follow the course at night mostly by the government lights,” Captain Hills recalled in 1948, “although on a clear night you can see the banks fairly well and profit by past experience. The greatest difficulty is fog. Of course, there are lights in the towns along the shore. You would think they would help a great deal, but actually they are a hindrance. Brilliant electric lights glare in the pilot’s eyes and obscure his view of the banks. The lights may be some distance back from the shore but it’s still a problem. It’s hard to discover sometimes where the water ends, and the land begins. That’s where the danger lies.”

Snags of the sort that doomed State of New York were a constant threat. In 1870, City of Hartford struck a submerged log on her downward run and stove in her bottom. She began to fill rapidly. Captain Mills rang the engineer for a full head of steam and made for the shallows while the crew worked furiously to pull up carpets, bedding, and furniture and haul them up to the main deck. When her tender Silver Star reached the stricken steamer, City of Hartford presented a pitiful sight, sunk to her guards with her fine Brussels carpets, tapestries, rosewood settees, and marble-topped tables all piled in heap on deck. Six feet of water filled her lower cabins. Passengers, many uncomfortably soaked, were ferried back to Hartford to catch the midnight train for New York.

But City of Hartford’s worst mishap was May 17, 1876, when the 276-foot sidewheeler plowed into the new railroad bridge at Middletown while running at night. The impact of the collision carried away several of the fixed truss spans, draping one across the steamer’s foredeck. A passenger in the ship’s barroom was just lighting a cigar when the crash came. He was hurled several feet in the air and thought he had touched off an exploding cheroot. The pilot was killed.

Steamboat interests had bitterly opposed a crossing at Middletown, thus the railroad was convinced the crash was intentional. But Capt. Russell maintained that the draw span was not lighted as it should have been. Others believe he confused a light on shore with one on the bridge, both of which were white. The case would end in a draw, the judge ordering both sides to split the damages. The positive outcome was that the federal government ordered all drawbridges in the future to be marked with red navigation lights.

Erik Hesselberg has been writing about the Connecticut River for twenty years, first as an environmental reporter for the Middletown Press, and then as executive editor of Shore Line Newspapers in Guilford, where he oversaw twenty weekly newspapers. He lives on the river in Haddam, Connecticut, and is at work on a book about Connecticut River steamboats.