An Indomitable Spirit

Colt Factory National Historic Site. Image Credits: Christopher Zajac (Colt Armory).Public Domain/Wikimedia (Samuel Colt).

Heading up the Connecticut River, just below downtown Hartford, the west bank reveals an incongruous vision. Eyes are pulled to a blue, onion-shaped dome, spangled with golden stars and tipped with a rampant colt finial. It tops a brick building that once housed a crown jewel of the Industrial Age. The colt is the signature icon of Samuel Colt, one of the most significant Americans ever born on the banks of the Connecticut. His enterprises took him all over the world, but he always returned to his hometown. In Hartford, he established his manufacturing empire, and built his mansion. He loaded a lot of living into his forty-seven years.

John Chester Buttre made this steel engraving circa 1855 of Samuel Colt holding his Colt 1851 Navy Revolver based on a daguerreotype by Philipp Graff taken between 1847–1851.

Sam Colt was born in 1814. His mother died when he was seven. His father remarried, and Sam went to work at a farm just down the river in Glastonbury. He brought with him his two most precious possessions, the flintlock pistol his grandfather carried in the Revolutionary War and “The Compendium of Knowledge.” It was a trove of mechanical and scientific information that stoked his inquisitive nature. He read about David Bushnell who invented the “Turtle,” the hand-powered submarine, which underwent her undersea trials on the Connecticut River. Bushnell’s work had a strong influence on Sam.

When Bushnell was a Yale student, he dabbled in underwater explosions. He successfully detonated a submerged device in a local pond. Fourteen-year-old Sam replicated this feat years later in Massachusetts. He vowed to blow up a raft on a lake as part of the town’s 4th of July festivities. The explosion was mighty, but the raft remained intact. Onlookers wound up soaked and covered with slimy mud. Sam’s penchant for pyrotechnics got him into further trouble at Amherst Academy. He was there to study navigation. His river upbringing had instilled a love of the nautical in the lad. Sam’s prep school career was cut short when he set a school building ablaze with one of his bombs.

His dad decided to ship him out as a common sailor, aboard the Corvo bound for Calcutta. Sam was not popular in the fo’c’s’le. He was flogged for pilfering sweets. But it was there that sixteen-year-old Sam had the revelation that would transform his life. In India, he came across a Collier pistol that could fire more than one shot without being reloaded. Sam considered its deficiencies. He had an epiphany that the Corvo’s steering mechanism and capstan held the key to designing a rotating cylinder that would align a cartridge with a gun’s barrel for successive shots. Sam took out his pocketknife and whittled a piece of wood into the prototype that would change the world.

He returned to the states and fabricated a pistol and a rifle based on his wood model. The pistol exploded, but the rifle functioned well. His dad subsidized these early efforts but refused further funding. Determined to paddle his own canoe, Sam set out with some scientific knowledge to generate start-up scratch. Since he was familiar with nitrous oxide, he put together a show and traveled throughout North America gassing audience members and declaiming erudite aphorisms. He billed himself as “Dr. S. Coult of New York, London, and Calcutta.” He later transformed the act into an interpretation of Dante’s Inferno featuring elaborate wax mannequins, actors, and pyrotechnics. His experience in show business honed Sam’s skills as a raconteur and self-promoter. Self-promotion became an important element of his eventual success.

Sam worked with gunsmiths in Baltimore to improve his designs and manufacture guns. When his products became workable, he travelled to England for patents. Returning to the United States, he secured US patents to manufacture his innovative weapons. The head of the Patent Office was a friend of his family and expedited the process. Sam was ready to produce guns large scale. He attracted venture capital and opened a factory in Paterson, New Jersey. There Sam configured the mass production of interchangeable parts. Output sputtered along, and Sam met with mixed success marketing his inventive firearms. Regulatory red tape prevented sales to state militias. An early order of seventy-five guns was cancelled when Colt could not produce on time. Sam ran into trouble with his backers. They didn’t appreciate his use of company funds for bibulous dinners with potential customers. Sam also felt he should dress well on the company’s dime in order to impress clients. Clients were not sufficiently impressed, and the company folded.

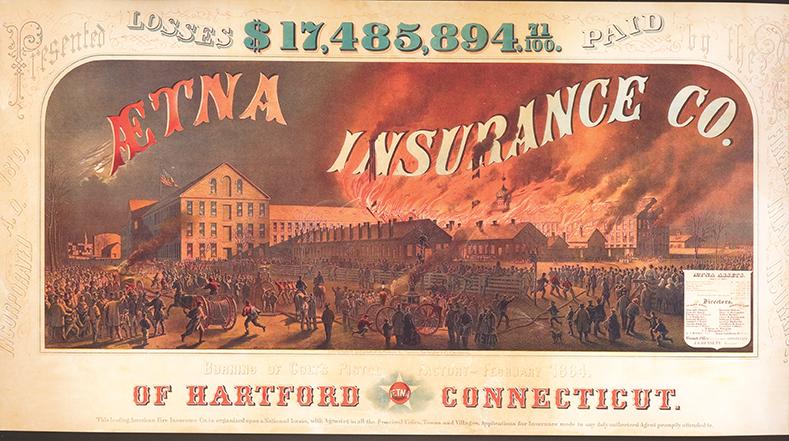

The Colt Factory fire of 1864 is portrayed in this poster lithographed by Ehrgott Forbriger & Co. for the Aetna Insurance Company advertising the $17,485,894.71 paid to Colt for the losses. Image Credit: Courtesy of Jim Griffin/The Sam and Elizabeth Colt Heritage Center (insurance company poster).

Hoping to stay afloat, Sam, inspired by Connecticut River inventor David Bushnell, looked under water. He worked with telegraph pioneer Samuel Morse to create a submersible mine detonated by electricity to blow up enemy ships. He demolished several vessels, but Navy funding never materialized. The project was abandoned. During this time, Sam’s brother John committed a grisly murder. Sam stood by his sibling throughout his trial, but a guilty verdict was rendered. John was scheduled for execution in New York’s Tombs Prison. On the morning he was to hang, he married his pregnant paramour, Caroline Henshaw. After a conjugal visit in his well-appointed cell, a fire broke out in the jail. When the smoke cleared, John was dead from a self-inflicted stab wound. It was generally acknowledged that Henshaw’s baby was Sam’s.

It was by the Connecticut River where Sam’s dreams came true. Sam moved back to his hometown and established Colt’s Patent Manufacturing Company in Hartford’s flood prone South Meadows. He hired men of genius and vision who developed the machinery to create some of the most iconic firearms in history. An order from the Texas Rangers for 1,000 pistols provided the springboard Sam needed to rise to the highest echelons of the Gilded Age. With a proven product, eminently affordable and extremely useful in the mid-19th century world, Colt was the right man in the right place and time. He began construction on a massive industrial complex capped with his signature blue dome. But the river had other plans. The Great Flood of 1854 coupled spring snowmelt with sixty-six hours of driving rain and devastated much of Hartford, including Sam’s building site. His detractors guffawed. Served him right to build in a swamp.

Armsmear, Samuel Colt’s former mansion on Wethersfield Ave. in Hartford, was donated by Colt’s widow, Elizabeth, in her will to become a residential community for senior women. The house is still governed by The Trustees of the Colt Bequest. Image Credit: Christopher Zajac

Undeterred, Sam vowed, “I will bind myself to exclude the river from the South Meadows.” Exclude it he did. He built an extended dike to protect his property and construction recommenced. The following year’s freshet was no match for Colt’s embankment. The River was held at bay, and Sam’s factory came to fruition. It included Vrendendale Dock from which ships could carry his wares around the globe and receive loads of natural resources. The dock also accommodated his private ferry. He used his political clout to charter a service to carry his workers across the River from East Hartford. Some of his captains went on to skipper the grand steamboats that ran between Hartford and New York.

Sam became a world traveler; he hobnobbed with kings, czars, and caliphs. He used his personality to sell guns worldwide. His demonstration at the Crystal Palace Exhibition resulted in international celebrity endorsements and made Colt a household name. Today, in France, a pistol is still called “le colt.” Sam was also a pioneer in product placement. He commissioned famed artist George Catlin to paint scenes featuring Colt firearms. Colt was known to play two sides against each other as he ginned up arms races. He would sell to opposing countries, and supplied both the North and South with weapons in the run up to the Civil War.

The Colt Walker six-shot percussion revolver that won Samuel Colt a contract for 1,000 pistols for the Texas Rangers. The .44 caliber black powder revolver was the result of a collaboration between Colt and Texas Ranger Captain Samuel Hamilton Walker built upon the earlier Colt Paterson revolver. The pistol was manufactured in Whitneyville, CT, by Eli Whitney Jr. Image Credit: Public Domain/Metropolitan Museum of Art Arms and Armor Collection

Colt expanded his holdings and built his personal fiefdom, Coltsville. It included Armsmear, his vast mansion, with its many gardens, lagoons, lakes, fountains, and pathways. He also built housing for his workers. These included the Swiss Village designed to attract German workers to weave willow into wicker products. Sam had planted willow to anchor his dike and realized that its shoots could turn a profit. Coltsville had its own brass band, school, militia, and beer hall. Colt’s recruitment of European workers drastically changed the ethnic makeup of Hartford. He was a pioneer of diversity in Connecticut.

An old smoke stack bearing the Colt name still stands over the old factory building. Image Credit: Christopher Zajac

On June, 5, 1856, the steamboat Washington Irving left Vrendendale Dock bound downriver to Middletown. Aboard were Colt, his bride to be—Elizabeth Hart Jarvis, and their wedding entourage. They were married at the Episcopal Church. After an extended grand tour honeymoon, they took up residence at Armsmear. Elizabeth and Sam set about gathering world art. Their collection would later grace Hartford’s Wadsworth Atheneum. They had four offspring, but only one, Caldwell, survived childhood. Six years into their marriage, Sam Colt died of gout. Elizabeth became the caretaker of his industrial empire and carefully curated his legacy. Through shrewd hirings, and a sharp eye on the bottom line, she steered the company into the 20th century. She was active in charitable and cultural organizations and was called “The First Lady of Connecticut.”

In Sam’s memory, she commissioned the Church of the Good Shepherd in Coltsville. It’s architecture is infused with images of pistols and rifles. She was a doting mother to Caldwell (Collie). She hoped that he would take the helm of Colt’s enterprises. At twenty-one, he designed a double-barreled repeating rifle, now among the rarest of Colt collectibles. But Collie trod the libertine path favored by second generation sons of Gilded Age magnates. He devoted his life to sailing, hunting, fishing, fine wine, and other hedonistic pursuits. He raced his schooner Dauntless across the Atlantic and brought her to the Connecticut River every autumn to hunt rails and carouse. He died under mysterious circumstances in Florida at age thirty-five. His mother promptly built a memorial Coltsville parish house with maritime motifs throughout. She installed the Dauntless in Essex as a shrine to her son and would visit it every fall. It eventually sank, but Essex still has the Dauntless Club and Dauntless Shipyard.

Today, Coltsville is on its way to National Park status. Visitors to the Wadsworth Atheneum marvel at the art in the Colt art collection. In this time of cultural reflection, Sam’s legacy, especially as it relates to the subjugation of indigenous people and issues surrounding the Civil War, is under re-examination. He was certainly no saint, but his legend lives on. Firearms are still produced under the Colt name. The guns he created are among the world’s most sought after collectibles. Biographies of Sam are churned out regularly. Elizabeth’s beloved Armsmear is now a residence for “senior women of limited income,” the result of her generosity and foresightedness. The Connecticut River still reflects Sam’s blue onion dome as the River he loved flows past his heritage.