The one-and-a-half-mile-long Great Island at the mouth of the Connecticut River is a wildlife preserve providing protected habitat for osprey and many other estuarian and coastal species. The Wildlife Area at Great Island in Old Lyme, Connecticut, was dedicated to the memory of Dr. Roger Tory Peterson in 2000.

Photo Credit: Christopher Zajac.

This magnificent estuarine expanse is both an aesthetic and utilitarian asset. Estuaries sequester about 20 percent of the world’s carbon, cleanse our waters, and provide comfort and sustenance to countless species, including our own. If you haven’t experienced this salty idyll, up close and personal, put it on your “to see” list.

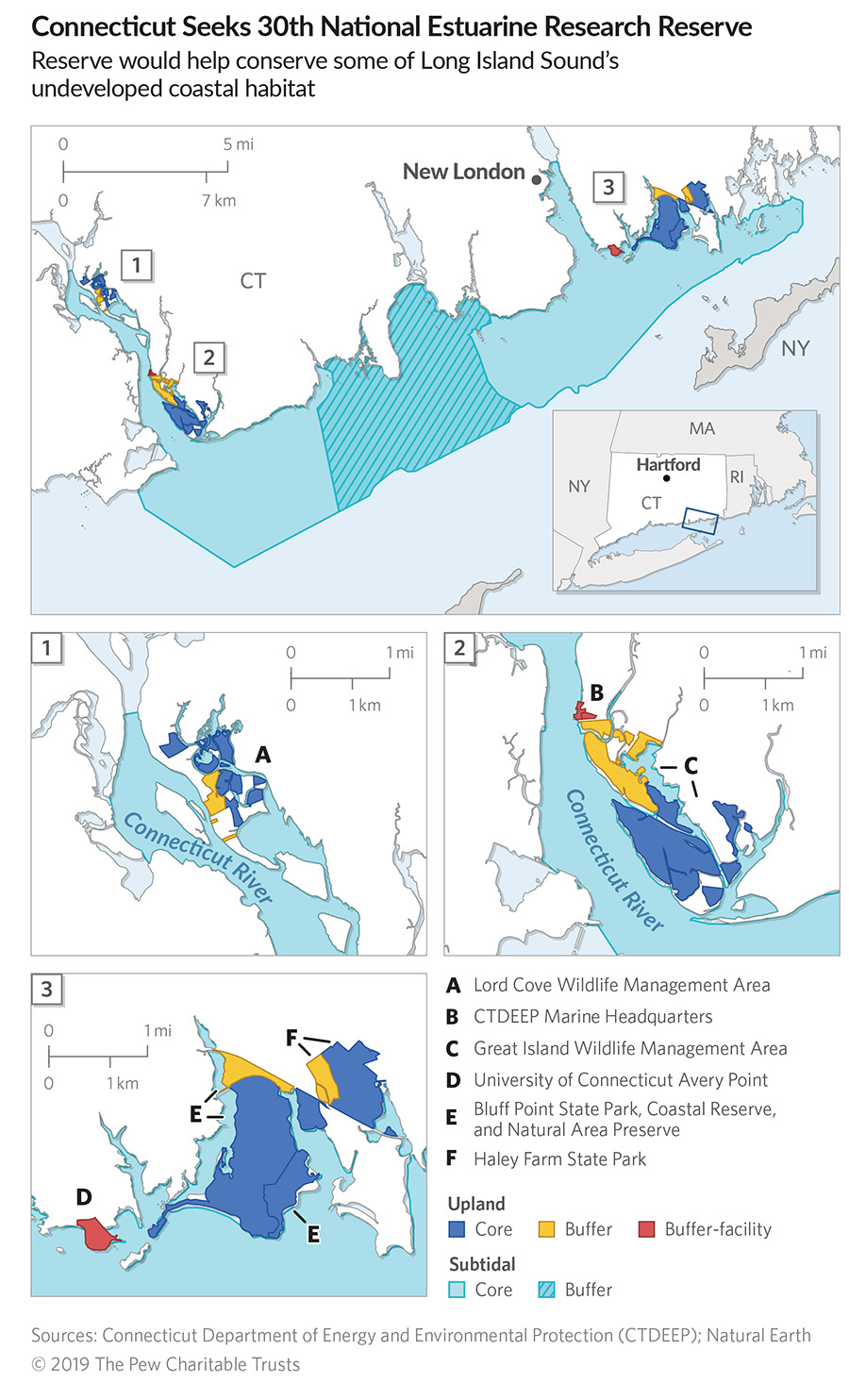

Two rivers, the Connecticut and the Thames, form the pillars of a proposed addition to a nationwide system of estuaries, known as the National Estuarine Research Reserve System, or NERRS. Established in 1972 by the federal Coastal Zone Management Act, this partnership between the National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) and coastal states now consists of 29 such reserves, with Connecticut and several others currently trying to be admitted to the network.

A snowy egret displays its plumage while perched on Great Island in Old Lyme, Connecticut.

Photo Credit: Kristofer Rowe

The mission of NERRS is to protect and study estuarine systems—and to foster a better understanding of their importance through educational programs for school children, teachers, and local officials and organizations. While NOAA would provide some $700,000 annually to Connecticut to support the new reserve—and the state would kick in another $300,000 or so—the proposal does not entail additional regulations, restrictions or acquisition of land.

Existing research reserves from New York to Maine already surround Connecticut. In fact, it is one of only two saltwater coastal states yet to become part of this nationwide system; Louisiana is the other. Like Connecticut, Louisiana is working to join the system.

The Connecticut NERR proposal, which has been percolating for a long time and has at least two more years of brewing time, consists of 80 square miles of shoreline, existing state-owned parcels such as Great Island and Bluff Point State Park, and a sizable chunk of Long Island Sound. From Lord Cove in Lyme, up the Connecticut River, it extends east as far as Mason’s Island in Mystic and south to just shy of the New York border in the middle of the Sound.

The University of Connecticut (UConn) would take the lead in managing the new NERR, working closely with partners, including NOAA and the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP).

“NERRS has a number of programs that each site is expected to support,” said Jamie Vaudrey, a professor of Marine Sciences at UConn. “A big part of this is the System-wide Monitoring Program, which involves deploying buoys that will keep track of water quality, sea level rise, weather and other data that is fed into the national system.” Vaudrey, who is also a member of the steering committee that has been developing the Connecticut proposal since 2015, added that other NERRS programs include: conservation training for local officials and organizations; and TOTE, or Teachers on the Estuary, professional development instruction, featuring more than 100 curriculum offerings on the environment for K-12 educators.

The Lord Cove Wildlife Management area of the proposed Connecticut National Estuarine Research Reserve can be seen on the left of this aerial view of the Connecticut River Estuary. Long Island Sound is on the horizon.

Photo Credit: Christopher Zajac

Also benefiting from these educational and training programs would be private organizations. Ralph T. Wood, another Connecticut NERRS steering committee member and secretary of the Connecticut Audubon Society, said, “We have spent a lot of time and energy on education for school children, and NERRS has developed an amazing storehouse of teaching and training materials that are free for its partners to use.” Wood, who is also president of Estuary Ventures, owner of this magazine, added, “They will provide a big boost for our educational efforts at the Connecticut Audubon Society.”

Kevin O’Brien, a supervising analyst with the Connecticut DEEP and another steering committee member, said that the relationship with NOAA would enhance his agency’s stewardship capabilities. “It’s a partnership in which the state’s existing regulations and control structure determines what goes on in the reserve,” he said. “What a NERR will do is give us the ability to take these unique, special places and do a bit more with them, in terms of conservation, to leverage funds to address coastal management issues.”

Erica Seiden, a manager of ecosystems and the NERRS program for NOAA, said that the proposed Connecticut NERR would add to ongoing research on estuarine ecology. “Each new NERR helps enhance the research being conducted in the other 29 reserves, on water quality and habitat, and specifically to understand the impact of inundation and sea level rise on our coastal habitats and their sensitivity to it,” she said.

Seiden and others pointed out that the Connecticut River remains relatively pristine for a big river, being the only major waterway in the Northeast without an urban port located at its mouth. In addition to providing habitat to such species as the bald eagle, the endangered Atlantic sturgeon, and commercially harvested fish species, the Connecticut Estuary Reserve also is a critical stopover for migrating birds, such as tree swallows, along the north-south Atlantic Flyway.

John Forbis, vice chairman of the Connecticut Audubon Society’s Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center in Old Lyme, began working on the site selection for the Connecticut NERR in 2013, and he vouched for the thoroughness of the process. “It took some time but it gave all of us an understanding of the power of the particular site that we have chosen,” he said. “We’re talking on a daily basis with consumers of the services that NERRS will offer, with organizations such as the Connecticut College Arboretum and local land trusts. We find the same intensity of support today as we did at the outset of the process.”

An aerial photograph of the UConn's Avery Point campus in Groton, CT.

The campus provides special emphasis on marine and maritime studies.

Photo courtesy of UConn Avery Point

At this writing a remote public comment meeting was scheduled for early August on options for the NERR designation for Connecticut. Additional public comment sessions will be held before an Environmental Impact Statement, including a Management Plan, is finalized. The final designation is anticipated in the spring of 2022.

As long and as multifaceted as the NERR process has been, its core purpose is straightforward, according to Kevin O’Brien: “The goal is to make these places more functional and beneficial to everyone, while maintaining or increasing the level of conservation—to make sure they are around for generations to come.”