Among the Birds

Among the Birds

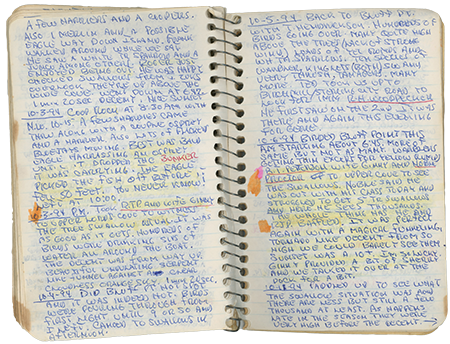

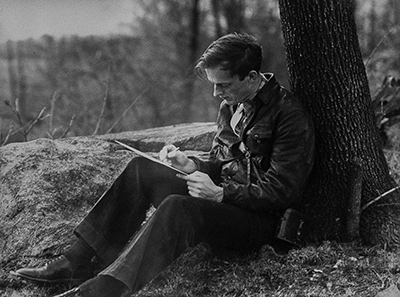

Roger Tory Peterson in his studio in Connecticut.

Image Credits: Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History (Woodthrush & Studio).

I still remember the first time I was handed a copy of Roger Tory Peterson’s A Field Guide to the Birds and my orientation as an incidental bird observer shifted to intentional bird identifier. I was 12 years old.

I had been in the habit of pedaling my bicycle to a seaward projecting sandspit where shorebirds collected on Long Island Sound. A steeply descending lane led out to a tongue of sand and marsh, where I could observe the comings and goings of long-legged waders, shorebirds, gulls, as well as songbirds. Understanding little about birds, I managed to master the art of grouping shapes and behaviors—the waders, the flitters, the lazy loafers, and the occasional high-flying “big birds” (raptors and vultures). But it wasn’t until I discovered the local Audubon Sanctuary and Nature Center and was given a copy of Peterson’s celebrated field guide (which fit conveniently in the palm of my hand) that I could make sense of the avian menagerie around me.

I have since learned that this pocket-sized guide with its unique “Peterson Identification System” was revolutionary for its time (1934). The standard tomes of numbingly lengthy text with overwhelming ornithological detail soon became relics. The Peterson guide sold out of its first printing of 2,000 copies in two weeks. By 1980, three million copies had sold, securing a frequent spot on the New York Times best-seller list. Over its nearly 90-year run, the Peterson’s bird guide has been translated into 13 languages, with six editions and over eight million copies sold. The famous bird guide also evolved into a hugely popular series of nature guides bearing his name on topics including wildflowers, ferns, trees, edible plants, butterflies, rocks, and stars.

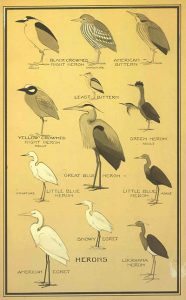

Peterson, an enthusiastic and passionate teacher-naturalist of children and adults, rather than a scholarly academically credentialed ornithologist, created this handy guide with exquisitely clear illustrations. He strived for simplicity to make birds and nature approachable, accessible, and understandable. His guides were teaching devices, not lofty works for dusty shelves for already converted experts. The Peterson bird guide was intentionally inexpensive and designed for the kitchen table, the windowsill, pocket, or backpack. Each species entry summed up in about four sentences the pertinent facts for identification. Each diagrammatic illustration featured a telltale black line to direct your eye to the key field marks. Spotting a small songbird creeping down a tree trunk? Find the illustration in a logical looking group, all facing in the same direction for easy comparison, and follow the black arrow to the bird’s eye. The Red-breasted Nuthatch is the one with the broad black line through the eye. In the same brief entry, one could immediately learn the home range, migratory route, bird song, and gender of the bird. With one book, an entire generation of bird noticing hobbyists emerged, and bird watching became a national pastime. More importantly, the field guide heightened the public’s interest in birds and natural history and stoked a movement to protect these newly appreciated feathered friends and their habitats.

Various art supplies and reference books at a workbench in Roger Tory Peterson's Old Lyme studio.

Image Credit: Bill and Gail Barber.

“Swallows and Swift” is from the third edition of A Field Guide to the Birds, 1947. The lines pointing to identification points for the different species was one of Peterson's clever creations.

Image Credit: Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History.

Audubon Girl

I was fortunate to enter my early teens when this awakening of noticing nature and caring for the environment seeped into mainstream America and became legitimate curriculum content in schools. On occasion, my middle school science teacher left the Bunsen burners and test tubes in the lab and led our class on so-called Nature Walks—a novelty during the school day and much appreciated by rambunctious, distracted seventh graders. Also, in this era emerged the first Earth Day (1970), when an entire school day was dedicated to awareness surrounding the needs of our ailing planet awash in pollution, waste, and environmental degradation.

At age 15, the North Shore Garden Club awarded me its annual summer camp scholarship and selected Hog Island Audubon Camp in Maine as my destination. I have since discovered, that in 1936, when Roger Tory Peterson served as its Director of Education, the National Audubon Society assigned him the job of scouting out the location for its first summer camp dedicated to training teachers and students in natural history. His reconnaissance led him ultimately to Hog Island as an ecologically worthy location. Peterson mapped out a trail system for the camp and became a legendary energizer educator constantly teaching and motivating his captive island audience about birds, nature, and conservation. He constructed a bird blind on a nearby island, Eastern Egg Rock, for camper viewing of breeding seabirds. By the time I attended Audubon Camp in 1973, Eastern Egg Rock’s purpose had shifted from education to research. Campers could visit this six-acre treeless island and learn about Project Puffin that has since successfully restored a population of 150 pairs of breeding Atlantic Puffins after the demise of the colony in 1890.

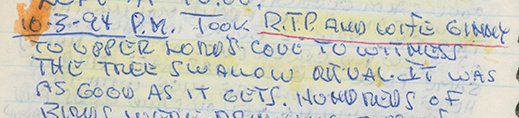

Notebook image courtesty of Henry Golet

Four decades after its founding, the Hog Island and Eastern Egg Rock total immersion camper experience, with its joyful and contagious 24/7 instruction, was another transformative catalyst to launch my career in environmental work. Incidentally, one of my children, like hundreds of others in this next century, also worked as a counselor on Hog Island eight decades after its founding.

My Hog Island experience confirmed that I was a lifer—an “Audubon Girl.” From high school biology and ecology teacher to Amazonian ornithologist, to winter seabird and breeding Osprey researcher, I lived and worked in ecological science, youth education, and environmental protection. In every case, and in every place, Roger Tory Peterson’s name was referenced due to his influence and impact in global natural history, ornithology, and conservation.

Peterson and Old Lyme

In 1954, Roger and his wife Barbara chose to move their home base out of Washington, DC. One motivator, it seems, was to escape the threat of a nuclear bomb that might target the nation’s capital. Peterson needed reasonable proximity to his Boston publisher, Houghton Mifflin, as well as galleries and other professional associations in New York City.

On the wall of Roger Tory Peterson’s Old Lyme studio was a large white poster with carefully ruled lines and neat printing as you might expect from someone who had spent his life producing meticulous drawings of birds and other wildlife. The makeshift calendar detailed deadlines, when he was to devote time for his painting, when he had a call to a congressman, lunch and dinner breaks, and more. You couldn’t help but notice in bold and sometimes colorful script, the occasional dates Roger had set aside for travel beyond Old Lyme. For the diligent artist, who was known to spend 12 hours a day in his studio, these trips to far off places were eagerly awaited, a tangible reward for all the hard work.

Perhaps his greatest journey was a 30,000-mile, 100-day trip, undertaken with his close friend James Fisher in 1953, which was chronicled in the acclaimed Wild America. There, in his lovely soft prose, you will note the exuberance that Roger felt in being footloose, with no schedule, wandering his beloved world of plains, mountains, forest, and wetlands where wildlife, not man, still reigned supreme.

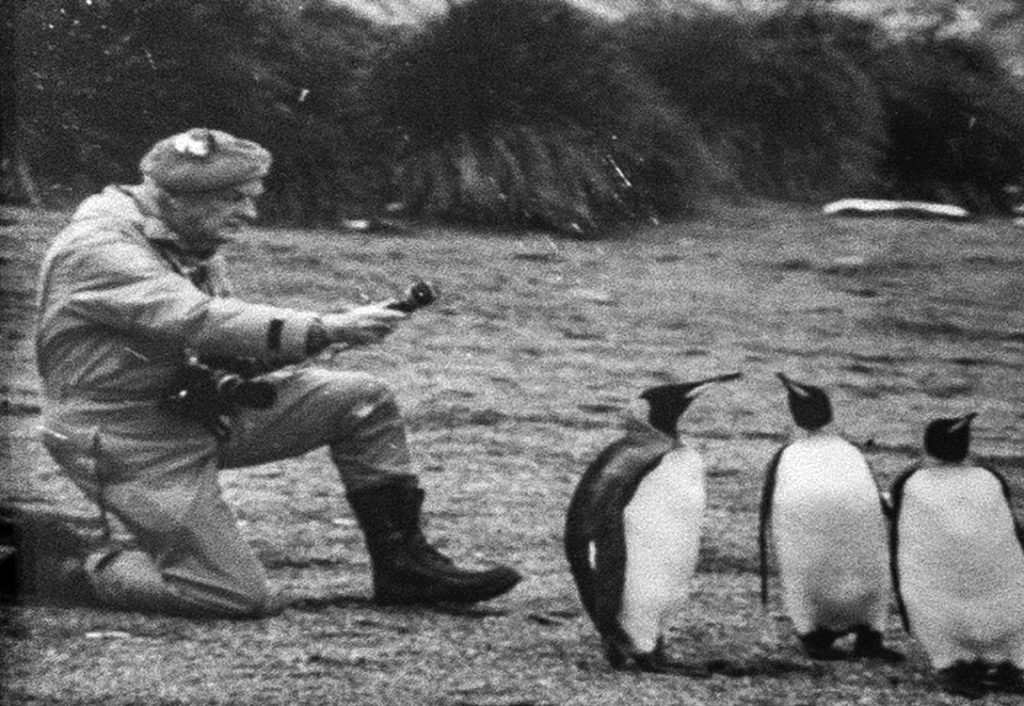

But as his career became established and his reputation more secure, he started taking more time breaking the confines of his studio. Influential in feeding his thirst for yet more travel and adventure was the travel empresario Lars Eric Lindblad who many now credit with inventing the concept of educational adventure travel to remote places around the world. Invited as a lecturer on board the pioneering ecotourism vessel MS Lindblad Explorer, he explored the Arctic, Antarctic, and many other exotic locations around the world, often with his wife. On these trips is where Roger came alive, enthralled by the majesty of nature, educating others about what they were witnessing, and being among “his people”—that kindred tribe of scientists, naturalists, and enthusiasts whose lives were as immersed in the natural beauty and wonder of the world as he was.

–Rob Hernandez

Various photographs of Roger Tory Peterson are on display at the Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center of the Connecticut Audubon Society in Old Lyme, CT.

Photos of the photos by Christopher Zajac

The town of Old Lyme, nestled at the mouth of the Connecticut River, half-way between the two cities, seemed like a good choice. This relatively tranquil and undisturbed nest site for a serious bird artist and author also featured a remarkable profusion of swallows, eagles, and ospreys. Equally alluring was the impressive diversity of bird species that seek out this significant estuarine ecosystem as a critical stopover or breeding and home range habitat on the Atlantic Flyway.

From his studio on their property on Neck Road, Peterson produced countless books, art, letters, and articles about birds and, seemingly, everything under the sun. His singularity of focus was legendary, to the point his associations with people were sometimes strained. Peterson did not know how, or care, to make idle talk. He seldom went to the grocery store or socialized. His world was his work.

One of his important contributions to science and the environment came from his awareness during the 50s and 60s of the precipitous decline of the previously thriving local Osprey population in his backyard, the Connecticut River Estuary. He erected the first Osprey nesting platform in 1962. Peterson’s alert and call to action for research, ultimately provided clear evidence leading to the nationwide ban of the pesticide DDT. Eradicating this organochloride pesticide, used since World War II, ultimately resulted in the revival of the Osprey, as well as the Peregrine Falcon, Bald Eagle, and Brown Pelican. Peterson testified before congress and sounded the alarm about massive bird mortality resulting from DDT, a harmful pesticide to bird reproduction. His words and actions mirrored similar warnings by his friend Rachel Carson in her powerful book, Silent Spring.

Peterson maintained a staggering pace of writing and painting in Old Lyme. He could go for weeks without leaving his property. He balanced a packed schedule of worldwide speaking engagements and ceremonies to receive 23 honorary doctorates, including one from Harvard University. Ever the avian documenter, Peterson, while attending a lecture of his colleagues, noted 24 bird species during the ceremony. The artist, writer, teacher, naturalist, conservationist, and scientist catapulted to fame, earning national and international acclaim with distinctions, including nominations for the Nobel Peace Prize and National Teacher of the Year. President Ronald Reagan awarded Peterson the Presidential Medal of Freedom. “Roger Tory Peterson was a far better scientist, and more productive and influential, than the majority of professionally trained scientists,” the Harvard ecologist E.O. Wilson once said. “He acquired and transmitted a great deal of new information about birds and made important contributions to the growth of ornithology and, therefore, science.”

Excerpt from Golet’s notebook. Image Credit: Henry Golet

Henry "Hank" Golet received this Great Horned Owl print, signed by Roger Tory Peterson, as a gift.

Image Credit: Image Credit: Henry Golet

Despite all the accolades, Peterson yearned to be regarded as a fine artist as well as illustrator. He admired the greats such as Robert Bateman and Guy Coheleach, and they inspired him to elevate his artistic work. Mill Pond Press in New York City recognized his undiscovered talent as an artist and contracted with him to produce high quality paintings to be available as limited edition, signed prints to be sold in galleries and frame shops across the country. These attractive and popular bird prints soon became prestigious decorative art in homes around the world.

Roger and Me

In 2011, I unexpectedly found myself, once again, in the territory of Roger Tory Peterson. My husband was offered a job requiring a move from Cleveland, Ohio, to Old Lyme, Connecticut. While considering this radical change in lifestyle and geography, I needed to appreciate the merits of my future home. Without hesitation I told my husband, “If Roger Tory Peterson could live in Old Lyme, Connecticut, so could I.”

In the months after we settled into our rental house outside the village, I was surprised to discover that the mythological Roger Tory Peterson of the last century was barely known by most residents of the town in this century after his death here in 1996. His significance had faded, as he was generally unknown to most adults younger than 70. More importantly to me, the name Roger Tory Peterson was meaningless to local school children. I looked for a statue or a named boulevard or some obvious feature of prominence for what I had to imagine was Old Lyme’s most famous resident, “the inspiration of the modern environmental movement.” Eventually, I found a faded sign at the Connecticut Marine Fisheries Division boat launch, just up from the mouth of the river, indicating that the Spartina marsh grass swath in view known as Great Island, and the surrounding estuary habitat was designated as the Roger Tory Peterson Wildlife Area.

“Herons and Bitterns,” 1934. This original plate was not included in the printed edition of the 1934 A Field Guide to the Birds, but the original work is just slightly different from the piece that did get used in the book.

Image Credit: Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History

Considering his global significance and contributions to natural history and conservation science, I was determined to resurrect his name more prominently in the region and continue his legacy. Building a team and seeking advice from interested estuary town residents, as well as regional and national professionals in conservation science, environmental advocacy, and ecological research, an idea took shape.

The Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center was launched in 2015, beginning with the highest standards possible for an environmental education program for schools and a free environmental lecture series for the general public. Propelled by a grant from the Community Foundation of Eastern Connecticut, the center initiated an ambitious environmental education program in the local schools. With a team of two tireless, part-time teacher-naturalists, we began by offering four-hour Science in Nature classes outdoors for all 3rd and 4th grade students in Lyme and Old Lyme. My introduction to each class was always the same. “What is an estuary, who is Roger Tory Peterson, and why do we care?” I realized quickly that our fledgling center had a long way to go.

“Ring-necked Pheasants,” 1977, for Mill Pond Press Company, is an original painting in the Peterson Collection at Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History. This is an example of several life-size species that Peterson painted for Mill Pond, and that became popular limited-edition prints.

Image Credit: Roger Tory Peterson Institute of Natural History

Ultimately, that virtual enterprise operating out of the back of my car has become a thriving new center of the Connecticut Audubon Society, with an office and education and meeting/visitor space in the commercial hub of Old Lyme. Today in 2020, the center educates thousands of school children each year in the estuary watershed towns of Southeastern Connecticut and the city of New London. It also offers public programs and college internships with a laser-focused mission to protect the environment through science-based education, research, and advocacy.

Roger’s rare genius, dedication, and insatiable enthusiasm drove people to a movement, not only to observe nature but also to protect it. His passion to inform and educate could not end with the wildly popular field guides. He awakened an entire generation of hobby and serious naturalists and environmentalists and inspired the next generation of conservation scientists.

The Connecticut River Estuary and Old Lyme, Connecticut, were the hallowed habitat of a 20th century giant in natural history, conservation, and some would say the “environmental movement.” Roger Tory Peterson’s early career began as an environmental educator for schools and for the National Audubon Society. His reputation and outright fame blossomed to national and international status in the decades following the publishing of his first bird field guide in 1934. His reputation as a naturalist for everybody, and tireless environmental researcher, communicator, and motivator was pivotal in the 20th century.

Celebrating his impact as a difference maker for the health of the planet, at a critical time, the Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center (RTPEC) emerged as an environmental center for Southeastern Connecticut, and was named in his honor.

There is a little reading area in the corner of the Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center in Old Lyme, CT dedicated to the center's namesake.

Photo by Christopher Zajac

From its inception in 2014, a group of estuary town residents and conservation professionals took hold of an idea to shape the RTPEC mission with Peterson’s principles of education, research, and advocacy, and with the ultimate goal of environmental stewardship and habitat protection. The Connecticut Audubon Society recognized the parallel missions of this nascent conservation group and the organizations merged.

In its first year, the RTPEC with three environmental educators (two half-time), launched CT Audubon’s award-winning, science-based, outdoor environmental education program, Science in Nature, for 35 school children in Essex. Fueled with support from foundations, business sponsors, and generous donors, the RTPEC now serves over 3,000 school children a year in area towns and the City of New London.

The staff includes a Director, Education Program Manager, part-time conservation biologist, a Pew Foundation fellow, college interns, and a cadre of experienced teacher-naturalists. Today the RTPEC offerings include a popular and free adult lecture series, public programs, and habitat explorations for all ages, as well as opportunities for field research, citizen science, and volunteer work. In this day of social distance, the RTPEC pivoted its education programs to produce a series of webinars, attended online by hundreds from all over the state and beyond.

Today, the temporary home of the RTPEC is a storefront in the Old Lyme Marketplace shopping center where classes, workshops, meetings, and curious drop-ins contribute to the center’s activity.

Expecting to create a permanent home, the RTPEC strives to educate the public and to serve as a strong voice for the environment, conservation, and stewardship of the critical habitats of Southeastern Connecticut, and the “bioregion” of the Connecticut River Estuary watershed. In so doing, the legacy of Roger Tory Peterson will continue well into the 21st century—and beyond.

–Eleanor Robinson

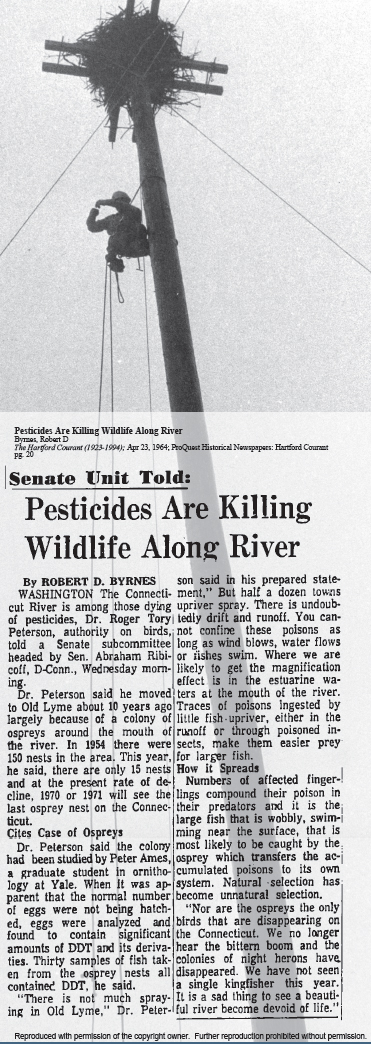

Ospreys, ca. 60s-70s

Photos by William Stekl

Roger Tory Peterson once said in National Geographic that it was the osprey colony around the mouth of the Connecticut River that drew him to Old Lyme. “I had an active eyrie [nest] in an oak on the ridge right back of my studio,” he wrote, “and my neighbors seemed to find a new status symbol in having their own eyries. Several landowners fixed cart wheels atop poles for nesting sites, and when they lured a pair, they boasted as shamelessly as Rhinelanders with storks atop their chimneys.”

When Peterson moved to Old Lyme in 1954, the town had 150 nests—something like 600 summertime birds. However, a decade later, only 15 nests remained. At that rate of decline, Peterson predicted ospreys would vanish from the Connecticut River Estuary by 1970 or 1971. “The Osprey—the crook-winged, chocolate and white raptorial bird—is in deep trouble,” The New York Times lamented at the time. “Everywhere, its survival now depends on human forbearance.”

The problem was DDT, an agricultural chemical widely used on crops, forests, and gardens, and employed in mosquito control as well. The DDT ingested by the osprey caused their shells to weaken and break prematurely, thus reducing their progeny. Rachel Carson’s seminal 1962 book Silent Spring described the dangers of widespread pesticide use, sounding a clarion call in the conservation movement. Peterson, a friend of Carson’s, suspected DDT was also to blame for nesting failures in the osprey colony at the mouth of the Connecticut River and Long Island Sound. Indeed, shells were found to contain significant amounts of the pesticide, as well as the chemical dieldrin, used to treat fabrics at textile mills upriver. Fish hawks, as osprey are known, were ingesting the toxins through their preferred food, the menhaden fish in whose fatty tissues the chemicals accumulate. And it wasn’t just ospreys that were suffering. “We no longer hear the bittern boom and the colonies of night herons have disappeared,” Peterson declared in 1964. “We have not seen a single kingfisher this year. It is a sad thing to see a beautiful river devoid of all life.” In 1972, the production and use of DDT was finally banned. However, in the meantime Connecticut River Ospreys were struggling.

Paul Spitzer, a soft-spoken college student and Peterson protégé, had watched the decline of these majestic birds with alarm. He had moved to Old Lyme as a boy and now, as senior at Wesleyan University in Middletown, where he majored in biology, was casting about for an original research project. In 1968, Spitzer was put in charge of the Old Lyme osprey study group, tasked with monitoring the few remaining nesting sites, and developing new ones. Knowing that osprey all over the world are considered to belong to a single species, Spitzer proposed a novel idea to save the pesticide threatened birds. This was an egg transfer program, in which eggs from less polluted areas such as the Chesapeake Bay, were swapped with those of Connecticut River birds.

“Roger and Barbara got behind my osprey egg switch experiments in 1968 and 1969, which I began as a Wesleyan undergrad,” said Spitzer in a recent interview. “With their backing, I persuaded the Patuxent Wildlife Research Center to fly north a sample of relatively “clean” Chesapeake osprey eggs for our remnant Connecticut nests. These hatched at their usual good rate, while the Connecticut eggs I sent south had their usual very poor viability. This reciprocal switch was dramatic evidence that the problem lay within the eggs—heavily contaminated with stable DDT residue, termed DDE. About this time, it was discovered that DDE thinned eggshells. As I expanded my New York-to-Boston osprey population survey in 1969, I discovered many such eggs collapsing under the incubating birds.”

“Like Carson, Roger assembled fragmentary but dramatic evidence (such as the extinction of the famous Hudson River peregrine falcons), connected the dots, and concluded that ecosystem application of stable, bioaccumulating DDT was creating ecological disasters,” Spitzer added. “Carson passed away in 1964. After that, Roger was prominent among those advocating a ban on DDT and other chlorinated hydrocarbon pesticides. He spoke at Federal hearings, wrote of the Connecticut osprey disappearance, and corresponded with others witnessing parallel disasters.”

In the decade following the banning of DDT, osprey populations slowly began to recover, and in 1985, the New York Times reported that 44 active osprey nests were observed in Connecticut. These yielded 72 osprey chicks—a 16 percent increase from 1984. By the summer of 1997, volunteers counted 172 osprey chicks hatched and fledged in the grassy salt marshes between Clinton and Groton.

Today, there are an estimated 125 osprey nests along the lower Connecticut River from East Haddam to the mouth, including 25 on Great Island in Old Lyme. Bald eagles have also returned, their huge stick nests crowning the tops of solitary trees. Great blue herons and white egrets are seen stalking the shallows, while the noisy chatter of the kingfisher is once again heard along the waterway Native Americans called Quinatucquet, the Long Tidal River.

–Erik Hesselberg