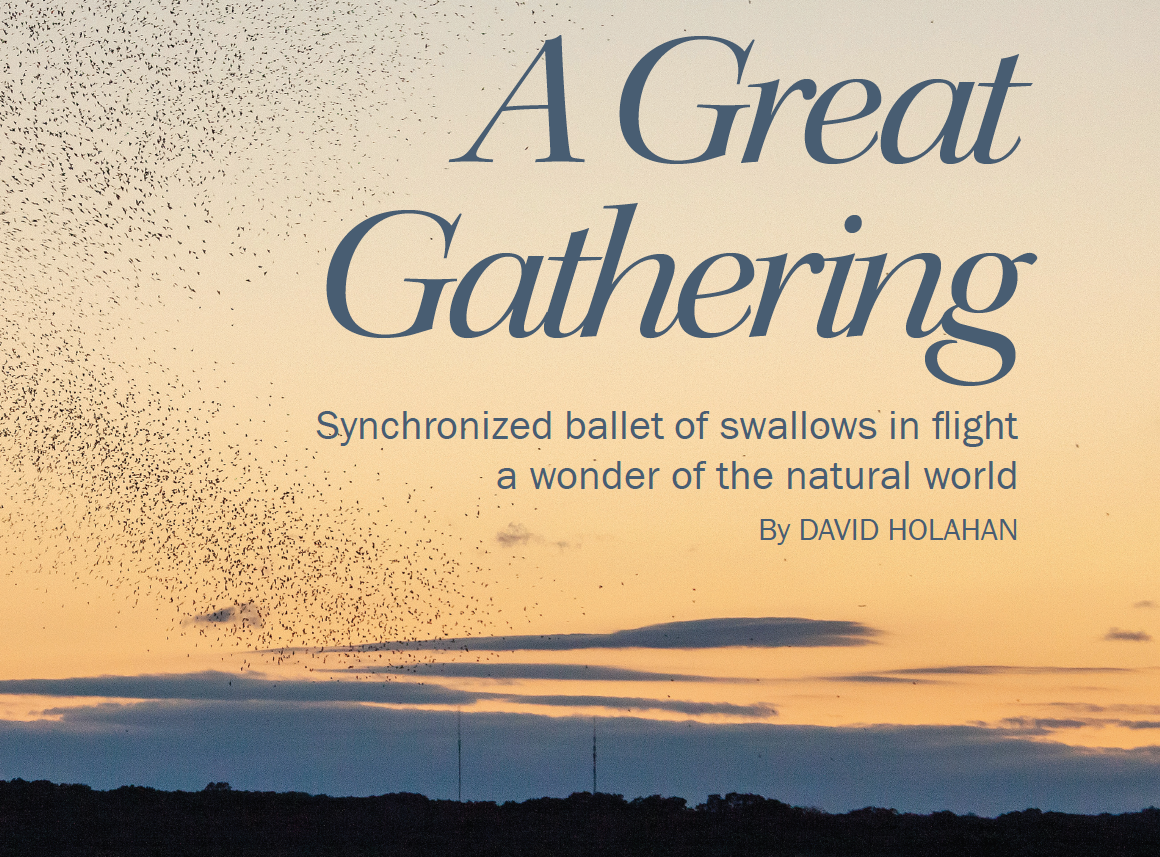

Tree swallows begin their descent in the waning twilight to roost in the phragmites of Goose Island in Old Lyme, Connecticut. The swallows dive in a tight spiral formation giving the appearance of a tornado touching down.

Image Credit: Diana Atwood Johnson

In countless numbers they assemble in the sky, in the quickening September dusk, to perform a swirling synchronized ballet. It is mesmerizing and indescribable; words cannot prepare the viewer.

Nevertheless, here goes: What begins slowly, as separate specks in the unbounded heavens, singularly unremarkable, slowly condenses into a whirring frenzy, a relentless massing of individuals, half a million or more—500,000 birds flying as one. This glorious congregation, now an animated black cloud, expands and contracts, sways and rotates, dips and rises for the better part of an hour—before disappearing from view in a sinewy vortex, funneling down into the marsh reeds as darkness descends.

All that is missing is narration by David Attenborough.

A tree swallow scoops up a sip of water in flight. Tree swallows can catch bugs in mid-air and drink water while in flight due to their acrobatic flight prowess. Image Credit: Diana Atwood Johnson

This annual gathering of mostly tree swallows in late summer at Goose Island—which is off the Old Lyme shore on the lower Connecticut River, just north of the Interstate 95—is recognized as one of the preeminent wonders of the natural world. For many, seeing it once, or twice, is not sufficient.

A tree swallow in flight. Image Credit: Kristofer Rowe

Every evening for three weeks or so in September and early October the birds attract a colorful flotilla of private and commercial craft—kayakers and canoeists, family cruisers, and pontoon boats, as well as sleek yachts and tour boats, 90 vessels by one count, which anchor just off the reeds. For some it is a floating cocktail party. Others celebrate from shore. It gets written up in the local media like the Kentucky Derby. The murmuration of the tree swallows is now well known hereabouts and beyond.

It was not always thus. Twenty-five years ago, nobody knew about it—outside of a smattering of locals who lived near or plied the big river. They would sit on their lawns, enjoy the sunset, and watch the dancing cloud of swallows. It was a well-kept secret.

Even the late Roger Tory Peterson, the world’s foremost bird watcher who lived nearby, was unaware of the murmuration for four decades. The late ornithologist and artist who made birding a national pastime with his popular field guides, moved to Old Lyme in 1954, not far from Goose Island. But it was not until the fall of 1994 that he first laid eyes on the swirling swallows. Peterson had witnessed just about every avian marvel on planet earth except this one. Henry Golet, who still lives by the river, introduced him to the flock—took him out on his boat in mid-October to see it. It was after the peak September murmuration, but still unforgettable. (In Peterson’s defense, his time in Old Lyme was devoted largely to long hours painting in his studio, leaving little time for bird watching locally.)

Like countless others since, Peterson was gob-smacked by what he saw. He confessed in Birdwatcher’s Digest: “In all my long lifetime of birding I have never witnessed a spectacle more dramatic than the twisting tornadoes of tree swallows I saw plunging from the sky after sundown this past October. And this was within four miles of my home near the Connecticut River, where this has probably been going on every October—all the 40 years I have lived here.”

In fact, no one knows how many Septembers the swallows have graced Goose Island. Henry Golet first noticed the phenomenon in the mid-1970s. Dr. David Winkler doesn’t know, and he’s been studying tree swallows for 35 years. Now professor emeritus at Cornell University and also on the editorial board of this magazine, he agreed with the guesstimate “from time immemorial,” with this caveat: “Remember, marshes are much more limited in extent than they used to be; they’ve become fragmented and smaller, so that is probably causing the birds to concentrate more than they might have in the past.”

But he added, “There is every indication that this drive for being together to roost is the major factor that makes these gatherings so large.” Indeed, tree swallow congregations along their migration route south, in Louisiana and Florida, are even larger than the Goose Island conclave—although the scenery can’t compare.

Andy Griswold, director of EcoTravel for the Connecticut Audubon Society, has been leading tour boats for members to Goose Island for 16 years. “When we first started going out, there was no one else doing it,” he said. “It was just us. The captain would get radio calls from people asking if the boat was in distress because we were hanging so near the shore. They thought we’d run aground.”

Decades of observing the swallows and scientific studies have answered some of the questions Roger Tory Peterson posed 26 years ago, for example: Is it the same birds, or new birds each evening? “From the Goose Island roost they go out each day to feed and build up their fat reserves and then they come back to the island at night,” Griswold said. “It is not a new set of birds. It’s the same birds with some additions coming in, and that’s what builds the numbers.”

As long as the insect buffet is open, the birds tend to linger in one place, according to Patrick Comins, executive director of Connecticut Audubon: “The migration is leisurely, they’ll stick around as long as there’s food.” But there is turnover, and the viewing some evenings is better than others, he added. When conditions are right, some of the birds move on, as others are arriving. “What they are doing is waiting for the first north winds to come,” Griswold said. “They take advantage of the tailwind to move them south, to save energy.” Many of the birds are bound for Central America, after all.

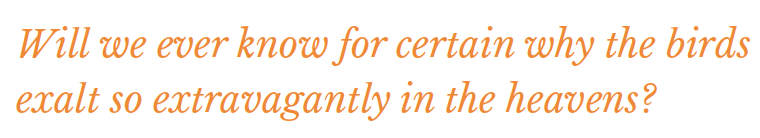

Spectators gather along the riverbank to watch the spectacle of the tree swallow murmuration over Goose Island during their fall migration. The amazing display draws thousands of viewers to the area on land, in kayaks and canoes, pleasure craft, and river boat tours every migration season.

Image Credit: Christopher Zajac

The big questions, of course, are how and why the swallows put on such a dense and dizzying display. Scientists actually have determined how they do it. Computer models driven by a few basic navigational rules can mimic the movements of the birds. The main keys are for each individual to be aware of and react with a handful of surrounding peers as well as to maintain a bird’s length of space (about six inches) front and rear, like cars on a busy freeway.

The why is a little tougher. Tree swallows seem to expend a lot of energy simply swirling about before going to bed for the night. Starlings gather in large evening flocks, too, but they don’t lollygag; they turn in quickly, without fanfare.

The scientific consensus is that the swallows and some other species gather and swirl about to be safe from predators, primarily raptors such as peregrine falcons and merlins. Mink and other carnivores may be lurking in the marsh reeds as well. “You started to have aggregations of birds in cluster flocks at night for protection,” said Dr. Frank Heppner, an emeritus professor of biology at the University of Rhode Island. “Some of the birds would stay awake and watch for predators, keeping the group safe. When you have more and more birds in the flock, they develop rules in a natural process for flying together, not necessarily for an evolutionary purpose.”

Others posit that the larger numbers do have a purpose, and that the aerial displays are tied to the concept of “safety in numbers,” perhaps even a sociable urge to merge, as anthropomorphic as that may sound. “I think they are developing a group adherence, a bonding,” said Griswold. “There also may be some nervous energy about not wanting to be the first ones to go down into a roost. And they also may not want to be the last ones to land either, so that’s why they all funnel down into the reeds together just as it’s getting dark.”

Dr. Winker attributes the group behavior to a “rough democracy of the flock,” explaining: “The thing that keeps them in line is that no single bird wants to be the only one that decides this is the spot and commits to that spot when the group is not following.”

Also, by staying together in such a large swarm each swallow lessens its chances of being the one taken by a predator. In addition, there is anecdotal evidence to suggest that the dense cloud of birds confuses or inhibits raptors. Henry Golet told Roger Tory Peterson that in all his years of watching the swallows he had never seen one taken by a falcon.

Tens of thousands, if not hundreds of thousands, of tree swallows begin to amass in the sky at sunset over Goose Island in the Connecticut River in Old Lyme, Connecticut. The mass of birds is so great it is sometimes detected by local weather radar.

Image Credit: Christopher Zajac</e,>

One would think, however, that a close congress of 500,000 birds would make an easy target. But Andy Griswold has seen peregrine falcons, which nest near Goose Island, fly straight into the black cloud of swallows and come up empty time and time again.

In addition to being admirable and compelling in aggregate, tree swallows also are quite handsome as individuals—with an iridescent deep-blue back, black wings and eye-patch, and snowy frontal feathers. They are cavity nesters and can often be seen during the spring in pairs or small groups roosting on power lines or garden fence posts. They will set up housekeeping in bluebird boxes, which the two species sometimes fight over. If September is prime time for tree swallow viewing, these songbirds actually start appearing in mid-summer on the lower Connecticut River—and linger, again in smaller numbers, well into the fall. A few stragglers have even shown up on the annual Audubon Christmas Bird Count.

And while their Goose Island numbers are impressive, all is not well with the species. As is the case with almost all North American birds, there are fewer tree swallows today than there were 50 years ago, according to a recent study published in the journal Science. A team of scientists from the Cornell Lab of Ornithology and elsewhere found that there has been a 29 percent drop in the aggregate population of birds on this continent since 1970. That equates to 3 billion lost overall, or some 60 million fewer birds each year.

Insect-eating species like tree swallows have been among the hardest hit, according to Dr. Winkler. “Aerial insectivores have had the most consistent declines in North America,” he said. “They definitely are in trouble. It may be that humans are better at killing insects than we used to be, but it also might be that Climate Change has altered the timing of the emergence of insect populations…In late summer and fall the birds may be coming up short on food.”

Viable migratory way stations like Goose Island are also keys to the health of species like tree swallows. It is hard to tell if the annual gatherings there have diminished in recent years, but the numbers definitely tail off dramatically as October progresses; and yet in 1994, when Roger Tory Peterson witnessed the swallow murmuration in mid-October, he described a still fulsome turnout, seemingly comparable to what viewers see today in mid-September. This suggests that, 25 years ago, there may have been more birds migrating through and that the peak migration season stretched further into the fall.

Over the years, Goose Island has remained the perfect way station for migrating tree swallows. Its 75 acres are protected by water and covered with phragmites, which the birds can hunker down in. Two owners, the Old Lyme Land Trust and the Potapaug Gun Club of Essex, share the site and are conservation organizations.

And yet last year, early in the migration season, observers were surprised to see a large segment of the species snub Goose Island in favor of the northern tip of Great Island, which is just south of the I-95 bridge—about as far south of it as Goose Island is north of it. The roost sites are less than three miles apart, but the change in behavior had people wondering.

Some questioned whether human attention was affecting the birds. On at least one occasion in recent years a drone could be seen hovering over the flock. Andy Griswold pointed out that this would affect the birds’ behavior and was therefore a violation of federal law protecting migratory species.

But as the peak September weeks rolled around last year, the flock had largely returned to its perennial haunt. Tree swallows are most comfortable in the air and don’t appear to be shy of their admirers. They often fly in and among the armada of boats, sometimes dipping down to take a sip of river water—or to belly flop into the water for a refreshing bath.

“They are pretty darn unconcerned with humans,” Dr. Winkler said. “When the number of roosting birds is smaller there probably is less consistency in where they end up on a given night.”

Roger Tory Peterson was 86 years old when he first saw the tree swallows gamboling above Goose Island. He had many questions but not enough time to answer them. He passed away less than two years later.

Some of his questions have since been answered or are still being investigated. The Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center in Old Lyme, a nonprofit educational entity that is part of the Connecticut Audubon Society, has partnered with the Cornell Lab of Ornithology to photograph the birds in an attempt to get an accurate count of their numbers using computer analysis.

In mid-October 1994, Peterson said that his friend and fellow birdwatcher Noble Proctor estimated that there were perhaps as many as half a million birds swirling above them. Peterson, however, conceded: “But who knows?”

The human compulsion to know is relentless. Modern weather radar can now pick up murmurations, and researchers are working on developing tiny solar-powered tags that will be able to track individual songbirds.

But some of Peterson’s questions may never be answered. Will we ever know for certain why the birds exalt so extravagantly in the heavens?

“It could be unknowable,” Dr. Frank Heppner admitted. “And I take a lot of enjoyment out of that idea. Some things you should just enjoy.”