A Connecticut River Odyssey

Lorna Eaton was sitting on the same porch, in the same spot, when they arrived. She lives, as she said, right “in the River,” since her house is on an island in the middle of the Connecticut River. While her address is Lunenberg, Vermont, some of her property taxes help with New Hampshire’s budget, as well. Her husband, Chester, died a while back, so the dairy farm was discontinued, but a neighboring farmer now leases out the farmland. Her older son lives on the property with his family. Behind the brick house was a tunnel to the River, part of the “underground railway” before the Civil War.

Lorna Eaton was sitting on the same porch, in the same spot, when they arrived. She lives, as she said, right “in the River,” since her house is on an island in the middle of the Connecticut River. While her address is Lunenberg, Vermont, some of her property taxes help with New Hampshire’s budget, as well. Her husband, Chester, died a while back, so the dairy farm was discontinued, but a neighboring farmer now leases out the farmland. Her older son lives on the property with his family. Behind the brick house was a tunnel to the River, part of the “underground railway” before the Civil War.

Jim Woodworth of Wethersfield, Connecticut, vividly recalls their arrival by sea. He met them at the South Windsor boat launch where he rewarded their efforts that day with BLT sandwiches. He then offered to drive them to their lodging for the night by way of the Great Meadow Conservation Trust with the ulterior motive of a possible grant to the Trust. In this, Jim was successful. The most important way the Trust could preserve land was through outright purchase at fair market value. Jim recalls the grant was instrumental “at a good time” in the purchase of a small tract to add to what is now 4,000 acres in trust.

Paul Franklin at his Riverview Farm in Plainfield, New Hampshire, hasn’t moved “one damn bit” since their visit. Paul headed west from where he was raised, “hit the Connecticut River, and stayed.” His farm, site of a former ferry crossing, allows him, and his wife Nancy, to grow apples and other items sold as “pick your own” or at their farm-stand. It’s not enough for a living for them, but it does “make a life” for them.

During their overnight stay in Cornish, New Hampshire, their hosts were John and Linda Hammond. The Hammonds operated a large canoe and kayak rental business at the time, which they have since discontinued. They also recently donated a conservation easement over their property. John is still a full-time farrier, shoeing draft and riding horses with his propane-fired forge, which he got after his coal-fired forge set fire to his pickup truck.

When they put in at Bellows Falls, Mary Lynch hosted a wonderful party for them, to which the neighboring Hartys rolled over their grill.

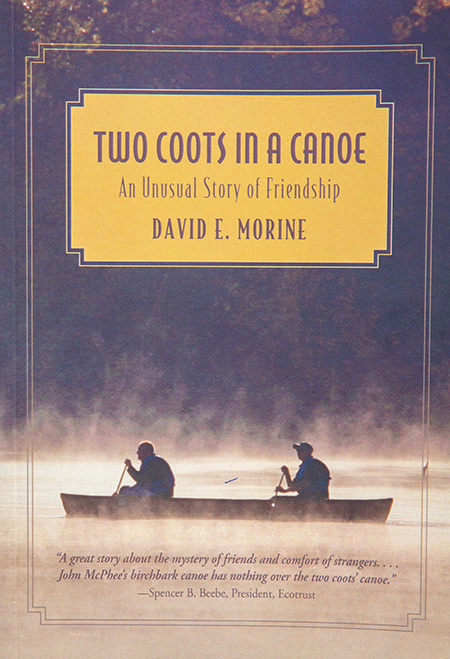

David Morine and Ramsey Peard stayed with 29 host “strangers” each night of their one-month, 400-mile canoe trip, in early summer of 2003, as they paddled from northern New Hampshire to Long Island Sound. Six years later, Morine memorialized this trip in his book, Two Coots in a Canoe. We’ll not try to do justice to this marvelous, humorous, and tragic account of a lifelong friendship that culminated in an amazing trip, other than to provide our readers with some information about the book, published by Globe Pequot Press in 2009.

Graduating with MBAs in 1969, Morine and Peard had been classmates and friends at the University of Virginia’s Darden School of Business. Morine then spent the ensuing 28 years as head of land acquisition for The Nature Conservancy. He left the Conservancy in 1990, and “has been writing ever since.” His friend and paddling companion, Ramsey, unexpectedly took his life some months after their canoe trip.

There is a certain magnetic attraction to the challenge of paddling the length of the Connecticut River. The effort is not at the level of scaling Everest or swimming the English Channel, but at least one person tried to swim the length of the Connecticut River in the late 19th century to publicize a newfangled lifesaving suit. [Estuary plans to write about several River-length paddle pilgrimages in the spring issue of 2021.] One even built his own canoe, using only the primitive techniques, tools, and materials that were available to native Americans, and he paddled upstream from South Windsor, Connecticut, living only on sustenance available to native Americans in eons past.

One decision of the two adventurers that makes Two Coots special was their decision to find overnight lodging along the way with total strangers. The Connecticut River Conservancy was helpful in that regard. On top of that, the ultra-successful businessman and conservationist, Dan Lufkin, authorized Morine to parcel out to small, deserving non-profits along the way a total of $50,000 in grants. Morine gave out seven grants to conservation entities along the River. He favored all-volunteer institutions with no paid staff or corporate edifice.

David Morine is an accomplished wordsmith as well as an avid conservationist. Mostly, he wrote about the trip itself, the challenges of the River and the characters they met along the way. His disarmingly simple narrative is interspersed with tantalizing bits of history and the local economy. He recalls a time when North Stratford, New Hampshire, was the capital of the New England timber industry and the source of much wealth for those in control, or when Vermont boasted it had “more cows than people,” or when dairy farmers received a government subsidy of two cents per pound of milk. About Bellows Falls, “Waterfalls are the most interesting part of any river. That’s where rivers get to flex their muscles and show the world what makes them great. With a drop of fifty feet, Bellows Falls had plenty to flex. Two hundred years ago, we would have seen hundreds of thousands, maybe millions, of Atlantic salmon packed in the pools below the falls, each summoning strength to attempt the climb. Along the banks, eagles, bears, catamounts, and, of course, people, would have been waiting to feast on the losers. And there would have been plenty of losers. In its heyday, Bellows Falls was a firm enforcer of Darwin’s survival of the fittest, but on this day, we saw nothing. Thanks to the dam, the Connecticut had no muscle to flex. Above the dam, the river was a placid lake; below it, an empty gorge. The falls were gone.”

Or when commenting upon the different ways that riverside towns adapted to the River: “Brattleboro’s turned its back on the river,” David said. “Clearly, that was a mistake. Towns that embraced the river like Bradford and Bellows Falls, seemed to be prospering. Towns that ignored it, like Woodsville and Windsor, seemed to be going nowhere. Making parks and green space along the river part of a downtown area capitalizes on a tremendous resource. Any city or town that doesn’t understand that deserves to fail.”

Looking back on the Morine-Peard odyssey, Dan Lufkin had this to say: “What made David’s idea work, it was personal. He knew people, the program. He didn’t start from scratch. It gave him a big leg up. It wasn’t just the money.”