Cave painting in Chauvet, southern France. Image credit: Claude Valette/CC BY-SA

Before initiating the venture that has become estuary Magazine, we conducted a brief survey of the topical preferences of our potential readership along the Connecticut River. Of the several choices that have become the magazine’s themes, wildlife was at the top in popularity, higher than the next closest topic, science and conservation. When responses to the birding choice are added, the combined wildlife category is the run-away favorite. That outcome made sense to us, especially considering the diversity of wildlife in the Connecticut River watershed and the fact that we, too, share this fascination. Who isn’t stirred by the sight in the wild of a moose, a doe and fawn, a black bear, a great blue heron in flight, or an eagle or osprey carrying prey, or by the sounds of a wood thrush, coyote, wood frogs or an owl, or by estuary magazine’s stunning wildlife photographs? But why? What is the source of this fascination with animals and other wildlife? Is there a scientific, perhaps evolutionary explanation? My investigation hasn’t yet yielded complete answers, but there are some revealing clues.

Archeology

Our ancient ancestors documented for posterity that they were animal watchers. On the walls of the caves in Chauvet, southern France, they drew pictures of many animals, which experts have deciphered to include both predators, such as cave bears, cave lions, wolves and panther, and prey, herbivores such as bison, musk oxen, horses, reindeer, several other species of deer, mammoths and rhinoceroses. One can imagine that these pictures, which have been dated to over 30,000 years ago, were art that celebrated survival: sustenance (identification of animals to eat) and safety (identification of animals that would eat ourancestors). Evidently, for our ancestors, animal watching had two necessary purposes: opportunity to learn the habits of their prey to improve hunting success and awareness of dangerous animals nearby and the learning of evasive tactics. Neither fits the definition of “fascination.” Humans today, however, have added more reasons for which fascination with animals and other wildlife becomes a more apt description.

Evolution

Humans are animals, too. We have similar lifecycle activities: birthing, nurturing, maturing, eating, eliminating, sleeping, reproducing, aging, and dying. One theory of our fascination with animals holds that we observe them, in their native habitats and in zoos, to discover deep origins of our current behavior. In short, we view animals as reflections of ourselves and we watch them to learn more about us.

Image Credit: Getty Images

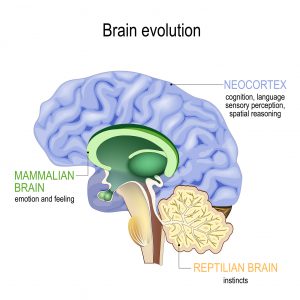

We know, for example, that the foundational construct of the human brain stem, the so-called reptilian brain, began with fish, reached a higher state in reptiles, and is found in many other animal species. The reptilian brain, which regulates vital body functions, is the seat of our autonomous “fight-or-flight” instinct, also shared with animals. It’s thrilling to see how the animal kingdom engages this instinct, particularly in mating rituals among competitive suitors and in actions taken to elude predators. Underneath, are humans really that different from animals in the wild?

Enter further evolution. Although in the main we share with animals the same five senses -- seeing, hearing, smelling, touching, and tasting, these senses have evolved to different degrees of responsiveness, compared with animals, as have other functions of our brains and, indeed, brain anatomy. The human brain today has developed two additional components, the limbic system and the neocortex. Part of our current fascination with animals comes from observing the extra prowess that some possess and from comparing our brain power to theirs. For example, the visual acuity of a raptor is 8 to 10 times that of a human; dogs can hear high-frequency sound that is out of range of human hearing; elephants and whales can hear very low-frequency sound; birds can see into the ultra-violet wavelength of the electromagnetic spectrum; pit vipers can interpret images in both the infrared and visible parts of the spectrum; some migrating bird species can navigate thousands of miles evidently by sensing and processing flux lines of the earth’s magnetic field; bats navigate by sonar; and the African elephant is believed to have the most sensitive sense of smell of any land animal. This species has 250% more olfactory receptors than a dog, which has 200% more olfactory receptors than a human.

In comparisons of brain power and function, we can find animals that excel in sensory reception (just enumerated), navigation, brain protection (avoidance of traumatic brain injury), density of supporting brain cells (glia), and neurogenesis (ability to generate new neurons). Thanks to the neocortex part of our brains, humans generally excel at advanced planning and decision making, consciousness and self-awareness, humor, appreciation of mortality, imagination, value judgments, and adapting to unstable environments. Nevertheless, it is fascinating to watch a wild animal, often lacking an opposing thumb and finger, adapt a stick or stone for use as a tool. It’s not uncommon to find a parking lot, road or bridge surface that’s littered with broken shellfish shells dropped there from on high by birds attempting to open them. And it’s also fascinating to watch schools of anadromous fish swim up fish ladders, which they have learned to use to surmount human-placed dams on their way upstream to spawn. (The story of fish in the Connecticut River will be expanded in a featured column in future issues of estuary Magazine.)

Another fascinating consequence of evolution that’s seen in animals is their camouflage. For example, the pitch and width of stripes on a zebra create an optical illusion, when the animal is running, that confounds a pursuing lion to the point that it stops the chase. In the Connecticut River watershed, rabbits, deer, birds, frogs, toads, snakes, and praying mantis, to name just a few species, often blend in indistinguishably with their environment, especially when they are frozen motionlessly to fool predators or to ambush prey. To protect themselves from predators, some species have adapted markings very similar to unpalatable or more dangerous counterparts; in the watershed, a prominent example is found in the viceroy butterfly’s mimicry of the monarch butterfly that is unpalatable to birds.

Comparison of a Viceroy butterfly (left) and Monarch butterfly (right).

Image Credits: D. Gordon E. Robertson/CC BY-SA and USFWS Midwest Region from United States/CCBY

Next time I will wrap up this blog with three other areas of investigation: Curiosity-driven Fascination, Entertainment with Purpose, and Health. The Entertainment with Purpose area is about birding, arguably the most popular of human fascinations with wildlife.