A pair of cedar waxwings on branch over the river.

Credit: Robert Winkler/Getty Images

In the last blog I identified what it means to be an environmental activist (i.e., one who takes action on behalf of the environment) by introducing four examples. One, George Perkins Marsh, a Vermonter, who lived over 150 years ago and is cited as the first person to sound the alarm in his book Man and Nature (1864) about the irreversible harm that humans were causing the environment. Another, the famed birder, artist, and conservationist Roger Tory Peterson, whose legacy, forged in Old Lyme, Connecticut, lives on in his meticulous field guides, paintings, and prints along with a cadre of disciples that are continuing his conservation work.[1] The third, a contemporary husband and wife team, who have had an outsized influence on the environment of their town and the surrounding CT River watershed. And, finally, Bill McKibben, an indefatigable warrior from Vermont, who—in countless books, lectures, organized conferences, and the website 350.org—persistently applies his skills in environmental journalism and advocacy to promote taking local, national, and international action against climate change.

What You Can Do to Become an Environmental Activist

Last time, we parted with my advice to first become informed about the state of the environment and then develop the conviction that you can make a difference to the environment by volunteering in an area that interests you. To acquire this background, I recommended reading Bill McKibben’s book Deep Economy: The Wealth of Communities and the Durable Future followed by the book The Necessary Revolution: How Individuals and Organizations Are Working Together to Create a Sustainable World by Peter Senge et alii.

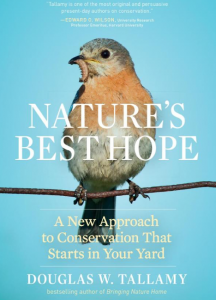

If you are still left wondering what you can do, you can start your involvement by looking no further than your personal lifestyle, back yard, or neighborhood. Douglas Tallamy’s book Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation that Starts in Your Yard (2020) offers recipes for accessible action.

If you are still left wondering what you can do, you can start your involvement by looking no further than your personal lifestyle, back yard, or neighborhood. Douglas Tallamy’s book Nature’s Best Hope: A New Approach to Conservation that Starts in Your Yard (2020) offers recipes for accessible action.

Next, start your engagement by joining at least one environmental organization that is involved in the Connecticut River, for example, the Connecticut River Conservancy, the Friends of Conte (the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge, which covers the entire length of the Connecticut River), a local land trust, or your state’s Audubon organization. The Connecticut Audubon Society, for example, has a nature center, the Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center, that serves the Connecticut River Estuary and surrounding towns with science-based environmental education, advocacy outreach and research facilitation.

I further recommend that you join at least one national organization, such as The Nature Conservancy, the National Audubon Society, Clean Water Action, or Rails-to-Trails Conservancy, as well as the Union of Concerned Scientists for the general accessibility of its environmental project results reported in their periodical Catalyst. Among the websites and publications of these organizations, you will also find information about state and national legislative agendas for environmental policy.

As you continue your education by reading the information that comes with your membership in the above-mentioned organizations, it’s time to choose a focus that interests you. Some examples include

- advocacy for effective public policy for the environment

- reducing your carbon footprint

- eliminating air, water, and soil pollution

- re-establishing native plant species

- habitat restoration, preservation, and invasive species elimination

- stemming bird population decline

- organic farming, community gardening

- environmentally compatible recreation

- living shorelines

- wetlands reclamation

- resiliency to sea level rise

- environmental education

- mentoring of the next generation of conservationists

On the other hand, if you live in or near an environmental-justice neighborhood that is plagued with noise; poor air, water, or soil quality; and has little green space, then you may decide to direct your activism to founding or supporting a community group that seeks environmental equity, that is, the same healthy environment that is enjoyed by the majority of neighborhoods in a state. A recent article in the Union of Concerned Scientists magazine, Catalyst, describes the establishment of a neighborhood action group to achieve equity.[2] In this case, the Little Village Environmental Justice Organization solicited the help of the Union of Concerned Scientists to measure the impact of a proposed development project in creating harmful air pollution of Little Village’s environment. The Justice Organization then developed, jointly with city government and local businesses, an improvement plan called the Little Village Industrial Modernization.

Finally, the following is a partial list of environmental organizations that have activities, which may be of interest to you, and provide training:

Invasive Plant Alas of New England (IPANE)

New England Wild Flower Society Plant Conservation

Project FeederWatch, Cornell Lab of Ornithology

Audubon Important Bird Areas (IBA) Program, National Audubon Society

______________________________

[1] There is an article about Roger Tory Peterson forthcoming in the fall 2020 issue of Estuary magazine.

[2] Union of Concerned Scientists, “UCS in the Community,” Catalyst, Spring 2020, p. 7