Where Have All the Birds Gone?

A recent study by Cornell University found that there are nearly 30 percent fewer birds in North America than there were in 1970. The team from Cornell analyzed data from long-term bird monitoring programs and also radar images of migration to conclude that there were nearly 3 billion fewer birds in North America than there were in 1970. While the study did not look into the causes of such declines, other studies have shown that the primary cause of bird population declines is the loss and/or degradation of habitat in the breeding, wintering, and migratory stopover areas. Other causes likely driving the losses include non-native invasive species, introduced predators, including cats, pollution, and collisions with windows, buildings, and tall communications towers. Disease and over-harvesting may be a factor in some of the bird’s declines. Of course, the twin threats of climate change and rising sea levels are greatly accelerating habitat loss and degradation.

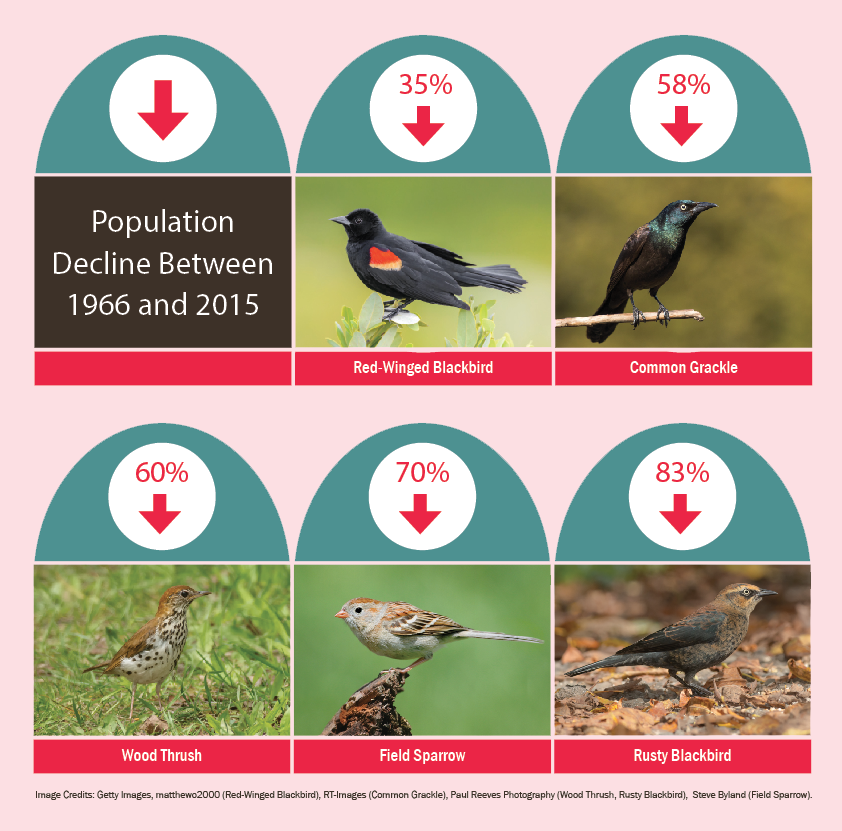

While the numbers are shocking, the overall finding isn’t that surprising to those of us who have followed bird population trends from surveys such as the Breeding Bird Survey, a long-term bird monitoring program of the US Fish and Wildlife Service. The results of that survey, as analyzed by the US Geological Service Biological Resources Division show that some of our most common and familiar birds have undergone dramatic declines in North America since the inception of the survey in 1966. For example, Red-winged Blackbirds have declined nearly 35 percent between 1966 and 2015, Common Grackles by nearly 58 percent, Wood Thrush by more than 60 percent, Field Sparrows by nearly 70 percent, and Rusty Blackbirds by nearly 83 percent.

Habitat destruction of wintering areas in the tropics is an issue that has received much attention as a cause of population declines for our migratory birds, but studies have shown that population declines in North American breeding areas are not even across the board geographically. It seems that population declines are most prominent in areas where breeding habitat in our own region has been degraded. It is easy to think of conservation as something that is needed in far away and exotic lands, such as the Amazon Rainforest, but a recent study by Connecticut Bird Conservation Research Inc. has shown that in areas of eastern Connecticut where large forest blocks remain mostly untouched by development that populations of many birds have actually increased over the past 30 years. Our actions right here in the Connecticut River Watershed can make a difference, good or bad, for our nesting birds of conservation concern. There are also conservation success stories. Populations of Piping Plovers, Osprey, Bald Eagle, and Peregrine Falcon have all been on the upswing thanks to local and regional conservation efforts and changes in national policy, showing that with a little help from us, nature can be resilient and bounce back.

The Connecticut River in particular holds critical nesting areas for many bird species of conservation concern. From nesting areas for the globally threatened Bicknell’s Thrush in the high peaks of the Green and White Mountains, to the lowland wetland haunts of the Rusty Blackbird in Vermont and New Hampshire, to the deciduous woodland homes of the Wood Thrush and Worm-eating Warbler in Massachusetts and Connecticut. Critical grasslands support nesting Bobolinks, Eastern Meadowlarks, and Grasshopper Sparrows, and globally significant wetland and beach habitats support important populations of Saltmarsh Sparrow and Piping Plovers where the river meets Long Island Sound.

To learn more about what you can do to help stem these declines in our area, please see:

www.ctaudubon.org/2020/01/10-actions-you-can-take-in-2020-to-help-connecticuts-birds/