RECLAIMING THE

MARSH

Rich Snarski examines Phragmites australis, also known as the common reed, in Lord Cove along the Connecticut River in Lyme, Connecticut.

A few miles upstream from where the Connecticut River merges with Long Island Sound is Lord Cove Preserve, a picturesque tidal marsh enjoyed by many outdoor enthusiasts. Kayakers and canoeists call Lord Cove a “corn maze on water,” marveling at its five miles of narrow, looping waterways.

Birders and photographers also frequent this watery paradise near Lyme, CT, hoping to catch a glimpse of such marsh birds as the secretive king rail, a least bittern, or maybe spotting a sedge wren, savannah sparrow, harrier hawk, or the federally threatened bald eagle. Mink, muskrats, and otters also call this verdant wetland home.

In addition to its natural beauty, Lord Cove is making a name for itself as a national example of a successful battleground for eliminating phragmites Australis, a Eurasian type of reed that’s plagued many salt marshes, ponds, streams, and estuaries across North America. This invasive reed had infested half of Lord Cove. Five years ago, Rich Snarski, a wetland scientist, and his wife bought 10 acres of land on Ely’s Meadow bordering Lord Cove, and dramatically changed the narrative.

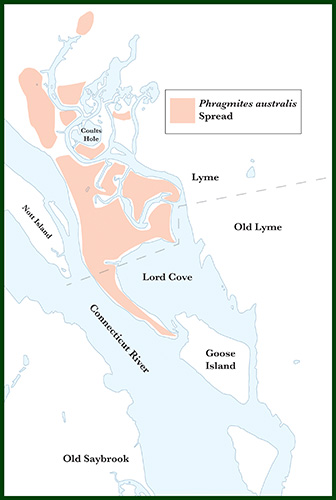

Rich Snarski shows a map depicting the extent of the spread of the invasive species in the Lord Cove area along the Connecticut River.

Snarski, it turns out, knew all about the ills of these invasive reeds. “The first thing we did was eradicate the phragmites on my property and the exotic invasive plants on the Connecticut riverbank,” Snarski said. He was also type cast for the role he would soon play in helping restore Lord Cove to a healthy native plant status.

For 30-plus years, this soft-spoken, rare plant expert worked with, and in many cases, brought together engineers, surveyors, municipalities, tribal nations, and private landowners to restore wetlands. He also designed and built innovative retention basins, using native plants with non-woody stems to remove stormwater pollutants.

Because of his work, Snarski knew that if his parcel of land was to become a healthy ecosystem, two things had to happen: native plants like smooth cordgrass, wild rice, cattails, water millet, and bulrushes needed to flourish on his property, and he would have to get rid of the phragmites. Otherwise, these non-native reeds would spread relentlessly, each stalk sending stolons (above-ground runners) out horizontally, by as much as five inches in one day, and rhizomes (below-ground rootstalks) shooting downward and outward by as much as 16 inches per year, causing devastating effects.

“When phragmites form a monoculture, they outcompete everything, growing up to 15 feet tall,” Snarski explained. “When that happens, the invasive reeds not only spoil scenic views for everyone, but impact area wildlife as well. Shoreline birds like herons, egrets, and the glossy ibis can’t land in the marsh to forage for insects and fish,” he said.

What’s extraordinary is that Snarski didn’t stop at the end of his property. Envisioning a “phrag-free” Lord Cove, Snarski stepped over his boundary and kept going. “After eradicating the phragmites on our property and seeing the positive outcome, we were inspired to eradicate the phragmites from the entire Lord Cove,” he said.

What’s extraordinary is that Snarski didn’t stop at the end of his property. Envisioning a “phrag-free” Lord Cove, Snarski stepped over his boundary and kept going. “After eradicating the phragmites on our property and seeing the positive outcome, we were inspired to eradicate the phragmites from the entire Lord Cove,” he said.

In 2016, Snarski and his wife Laurie, by now herself a converted “phragmites fighter,” spent days trudging across half of Lord Cove fighting mosquitos and pushing their way through some 240 acres of dense, almost impenetrable patches of non-native reeds, to map their locations. They also listed any rare plants they found.

Dave Gumbart, director of land management, and Sophie Duncan, land steward with The Nature Conservancy, plant one of 25 young American Elm trees in Lord Cove, near the Connecticut River.

Snarski then organized an on-site meeting with representatives from five different local, state, and federal agencies and organizations to review the map that he and his wife had prepared, and to talk about how they could form a coalition to rid Lord Cove of phragmites.

To Snarski’s total surprise, they all thought the idea was a good one.

The group, which would later loosely call themselves the “Coalition of Phragmites Fighters,” included the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (DEEP), The Nature Conservancy (TNC), The US Fish and Wildlife Service (USF&WS), the Lyme Land Trust, and the Connecticut River Gateway Commission.

Both DEEP and TNC jointly owned about 90 percent of Lord Cove and had a long-standing history of battling phragmites, prior to Snarski’s arrival.

According to Roger Wolfe, a wetland restoration and mosquito management coordinator for DEEP, “We started controlling the 220 acres of phragmites in Lord Cove in 2001 in a joint effort with TNC.

We got a three-year grant from the US Fish and Wildlife Service and a number of other contributors and had good control of the phragmites after three years,” Wolfe said.

Wolfe noted TNC had some additional funds and continued spot treating Lord Cove for several more years, with one last treatment in 2008. “Then the money dried up, the phragmites were left alone for 9–10 years, and they grew back with a vengeance,” he said.

“Rich has been instrumental in resurrecting this project,” Wolfe noted. “It is not often that we get to work with someone—and I include the other stakeholders here—with a real talent for identifying plants and a zeal for native habitat restoration.”

What makes this story so fascinating and perhaps instructional for others wishing to preserve a natural place like Lord Cove, is these individuals became a “Band of Brothers.” They partnered. In this case, they formed a “Coalition of Phragmites Fighters,” with each member bringing a unique set of skills to the table, and they respected each other’s talents. Finally, they admired Snarski’s vision, enthusiasm, and leadership.

Other individuals critical to this mission were Dave Sagen, private land biologist for USF&WS, Dave Gumbart, director of land management for TNC, Torrance Downes, lead staff person for the Connecticut River Gateway Commission, and John Pritchard, board member of TNC and president of the Lyme Land Trust.

Officials with Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection survey phragmites in Lord Cove on the back of an amphibious Marsh Master machine, used to mow the non-native reeds.

“Rich was the one that was able to tie us all together and keep us moving in the right direction,” said Sagen, who drove an ingeniously designed tank-sized amphibious mower, called a “Marsh Master.” This unique machine was able to navigate the marsh muck and cut down the phragmites.

Gumbart was instrumental in getting TNC to donate $16,000 toward the new project. An encyclopedia of knowledge about flora and fauna of the Connecticut River Valley, Gumbart and his assistants also helped the coalition by planting 25 young elm trees, bred from survivors of Dutch elm disease, along the riverbanks of Lord Cove.

Downes helped approve a grant of $30,000 in matching funds to Snarski and the coalition from the CT River Gateway Commission, an organization with a goal of preserving the aesthetic and natural ecological beauty of the Lower Connecticut River Valley.

“Rich is such a respected wetland scientist that when he comes before a board, he has the credibility and reputation. You can trust what he says,” Downes said.

“Rich is such a respected wetland scientist that when he comes before a board, he has the credibility and reputation. You can trust what he says,” Downes said.

Suzanne Thompson, chairman for the Gateway Commission, also was complimentary of Snarski and the coalition. “Here was a local approach that people were coming together to deal with invasive weed problems, and we lauded their efforts,” she said.

Lastly, Pritchard helped Snarski raise $30,000 to match the Gateway Commission’s grant. “We invited everybody who lives on Lord Cove, or over it, to come to my place for a fund-raiser, and we did raise the money to match the grant,” he said.

It took three years for the coalition to eradicate and control almost all the phragmites in Lord Cove.

“What makes this project different is it is long-term, and we’re not going to walk away from it,” Snarski said. And because of the coalition’s efforts, now many native plants in Lord Cove will thrive and wildlife will have food and natural cover and be able to return to this attractive marsh land.

Bill Hobbs lives in Stonington, CT, and can be reached for comments at whobbs246@gmail.com.

Lord Cove is making a name for itself as a national example of a successful battleground for eliminating phragmites.