The tranquility and stunning grandeur of the Connecticut River inspires poets, artists, and musicians. It also attracts picnickers, boaters, and tourists seeking fun and adventure. Like all rivers, however, the Connecticut River is influenced by forces of gravity that move water from source to terminus, or in this case, the half mile of vertical drop from Canada to the River’s mouth at Long Island Sound. Over its 410-mile serpentine course, 35 major rivers and 148 tributaries feed the main stem of the river. The sheer volume of water cascading toward the mouth and emptying into Long Island Sound is noteworthy. A fire hose of fresh water spills out 20,000 cubic feet per second, which contributes 70 percent of the fresh water in the Sound. But for all of the statistics and superlatives associated with this heavy weight waterway, the final, brackish 35 miles of the Connecticut River earns ultra-varsity status for its ecological importance as an estuary of regional and even international distinction. The Connecticut River Estuary is a much-heralded alluvial end point and tidal wetland mosaic. Its significance is measured partially by the properties of the water itself and by the spectacular profusion of biodiversity that is documented year-round by casual observers, serious nature observers, and scientists. A constant supply of organic material suspended in the water column from upriver and its vast watershed, permeates the relatively undisturbed tidal habitat at the mouth and fuels all levels of the food chain. Avian superstars like Peregrine Falcons, Bald Eagles, and Ospreys, and even two species of Sturgeon are attracted to this habitat hot spot for New England, similar to the species magnet of a tropical rain forest or a coral reef in more equatorial regions. Here, at the “meeting of the waters,” where incoming tidal and salty water mixes with the outgoing torrent of fresh river water, the sheer energy of the current and tides and the flux of sand, sediment, and detritus make the Connecticut River Estuary an ecological and hydrodynamic powerhouse among the great river deltas of the world, including the Amazon.

The tranquility and stunning grandeur of the Connecticut River inspires poets, artists, and musicians. It also attracts picnickers, boaters, and tourists seeking fun and adventure. Like all rivers, however, the Connecticut River is influenced by forces of gravity that move water from source to terminus, or in this case, the half mile of vertical drop from Canada to the River’s mouth at Long Island Sound. Over its 410-mile serpentine course, 35 major rivers and 148 tributaries feed the main stem of the river. The sheer volume of water cascading toward the mouth and emptying into Long Island Sound is noteworthy. A fire hose of fresh water spills out 20,000 cubic feet per second, which contributes 70 percent of the fresh water in the Sound. But for all of the statistics and superlatives associated with this heavy weight waterway, the final, brackish 35 miles of the Connecticut River earns ultra-varsity status for its ecological importance as an estuary of regional and even international distinction. The Connecticut River Estuary is a much-heralded alluvial end point and tidal wetland mosaic. Its significance is measured partially by the properties of the water itself and by the spectacular profusion of biodiversity that is documented year-round by casual observers, serious nature observers, and scientists. A constant supply of organic material suspended in the water column from upriver and its vast watershed, permeates the relatively undisturbed tidal habitat at the mouth and fuels all levels of the food chain. Avian superstars like Peregrine Falcons, Bald Eagles, and Ospreys, and even two species of Sturgeon are attracted to this habitat hot spot for New England, similar to the species magnet of a tropical rain forest or a coral reef in more equatorial regions. Here, at the “meeting of the waters,” where incoming tidal and salty water mixes with the outgoing torrent of fresh river water, the sheer energy of the current and tides and the flux of sand, sediment, and detritus make the Connecticut River Estuary an ecological and hydrodynamic powerhouse among the great river deltas of the world, including the Amazon.

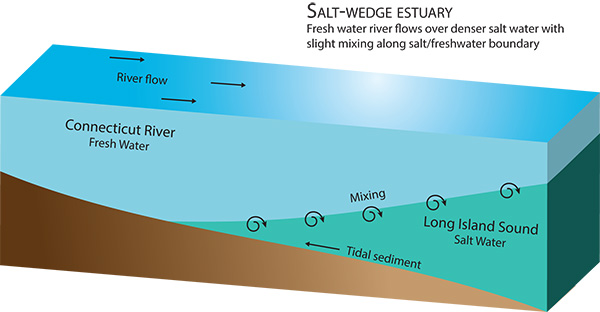

In and around this aqueous mixing bowl, a menagerie of flora and fauna seeks shelter, breeding sites or a strategic migratory stopover place critical to their sustainability. When this meandering course of river water approaches its terminus, the diurnal pulse of the incoming tides creates a formidable wedge of salt water in the water column. The density of the waters is different, creating a layering of nutrients and phyto and zooplankton communities. Ultimately, this aqueous stratification enhances the role of the Connecticut River Estuary and its salt marsh margins as important nursing grounds for fish, haven for juvenile fish, and a critical migratory highway for fish including Menhaden, Shad, and Herring.

In and around this aqueous mixing bowl, a menagerie of flora and fauna seeks shelter, breeding sites or a strategic migratory stopover place critical to their sustainability. When this meandering course of river water approaches its terminus, the diurnal pulse of the incoming tides creates a formidable wedge of salt water in the water column. The density of the waters is different, creating a layering of nutrients and phyto and zooplankton communities. Ultimately, this aqueous stratification enhances the role of the Connecticut River Estuary and its salt marsh margins as important nursing grounds for fish, haven for juvenile fish, and a critical migratory highway for fish including Menhaden, Shad, and Herring.

Illustration of Atlantic sturgeon.

Image Credit: Getty Images, Dorling Kindersley

The river mouth also features a formidable sediment plume that fans out for miles into the Sound. This shelf of silt with shifting sandbars has been the most important physical factor in keeping the Connecticut River Estuary relatively natural and undisturbed. Missing is the artificial hardening of the riverbanks in the form of jetties, seawalls, and urban port city infrastructure typical of major deltas in the world. The geometry of the river is relatively unaffected by human intervention. Consequently, most of the delta is still natural. This gives the estuarine ecosystem a chance to absorb storm water surges, prevent erosion, and let nature flourish. According to the Ramsar Convention on Wetlands of International Importance, “the lower Connecticut River, beginning at its mouth, contains one of the least developed or undisturbed large river tidal river system in the entire United States and the most pristine large-river tidal marsh in the Northeast.”

An extreme, visible example of the sediment plume Sept. 2, 2011, about a week after Hurricane Irene soaked New England captured by NASA satellite. Image Credit: USGS/NASA Landsat

This estuarine kaleidoscope of hydrology, geology, and biology attract world-renowned scientists conducting multi-million dollar research in what is regarded as a living lab. Of scientific interest is the array of biotic (living) and abiotic (non-living) properties of this complicated interface of water and land. Be it long-term monitoring or more crisis driven research, scientists are attracted to the Connecticut River Estuary to study features like the water column itself, the sediment, the underwater acoustics, the benthic invertebrates (clams and worms living on the river bottom), the aquatic vegetation, the salt marsh grasses, and numerous bird species including the federally endangered birds and fish that rely on this ecosystem for survival.

The Connecticut River flows under the I-95 Baldwin Bridge and Amtrak rail bridge between Old Saybrook and Old Lyme, Connecticut.

Scientists from universities and institutions including, Yale, Boston College, Wesleyan, U/Mass Amherst, Cornell, Connecticut College, UConn, and the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute conduct their investigations in research vessels, Zodiacs, kayaks or along the banks in rubber boots. A variety of federally endangered or threatened species are the focus of researchers in the Connecticut River Estuary. Among them are Roseate Terns that forage for abundant fish at the mouth and Piping Plovers that nest on sandy beaches fringing the estuary. UConn ornithologists are also studying the dwindling population of Salt Marsh Sparrows nesting in the Connecticut River Estuary marsh grasses that are currently flooding more frequently with epic tides. The Cornell Lab of Ornithology directs another avian project with local facilitation by the Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center. In question is the exact quantity of migratory Tree Swallows descending on a roost site on an uninhabited estuary island. It is guessed that over half a million Tree Swallows roost on Goose Island each night in September and scientists want to learn more about this annual phenomenon of nature. Ichthyologists are also studying the Short-nosed and Atlantic Sturgeon that travel upriver from the ocean and return to the estuary to feast on the cafeteria of invertebrates living in the organic material accumulated on the river bottom. The National Marine Fisheries Service has designated the Connecticut River Estuary as a “habitat of critical importance” for the Atlantic Sturgeon.

Osprey in flight along the Connecticut River.

“A million pounds of mud come down the Connecticut River every year,” says Dr. Wayne Geyer a Senior Scientist at the Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute who tracks the peculiarities of the salt and fresh water layers of the Connecticut River Estuary. It is this precious “mud” that fuels every level of the food chain that flourishes in the Connecticut River Estuary. The organic material suspended in the water column and deposited in areas like the salt marsh grasses sustains this exceptionally vital estuarine ecosystem, second to none in New England.

The mouth of the Connecticut River, with its plume of sediment and life supporting estuary and wetlands has also garnered the attention of the federal government. The National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration (NOAA) has recently identified the Connecticut River Estuary as a potential site worthy of inclusion onto a rarified list of 29 estuaries in the United States designated as National Estuarine Research Reserves (NERR). The designation would attract scientists and strengthen the potential for funding for continued research, education, and stewardship of the Connecticut River Estuary. Working with the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection (CT DEEP), UCONN, and environmental groups like the Connecticut Audubon Society, NOAA is currently reviewing this important initiative, which would designate the Connecticut River Estuary as the first NERR in Connecticut.

Humans are attracted to the estuary for its beauty and tranquility, but beneath the serene vista stirs a life force and aquatic energy that is best appreciated by migratory herring, filter feeding clams or foraging Sturgeon. The estuary is an ecological jewel that plays a critical role in contributing to the biodiversity of our region and thus, to life on earth.