“Come to the woods, for here there is rest,” wrote John Muir, the pioneering environmental activist and writer. “There is no repose like that of the green deep woods.” Few knew the healing power of nature better than Muir (1838–1914), whose deep connection with the outdoors was forged through a convalescence. It was in March of 1867 that the Sottish-born Muir was working in a wagon wheel factory in Indianapolis when he suffered a serious eye injury. Confined to a darkened room for six weeks in order to regain his sight, the 28-year-old Muir, who had studied botany in college but never graduated, was forced to reflect on his life and his purpose. It was during this period of solitude, Muir says, that he determined “to be true to himself” and follow his dream of studying plants, immersing himself in nature and the outdoors. “This affliction has driven me to the sweet fields,” Muir later wrote. “God has to nearly kill us sometimes, to teach us lessons.”

“Come to the woods, for here there is rest,” wrote John Muir, the pioneering environmental activist and writer. “There is no repose like that of the green deep woods.” Few knew the healing power of nature better than Muir (1838–1914), whose deep connection with the outdoors was forged through a convalescence. It was in March of 1867 that the Sottish-born Muir was working in a wagon wheel factory in Indianapolis when he suffered a serious eye injury. Confined to a darkened room for six weeks in order to regain his sight, the 28-year-old Muir, who had studied botany in college but never graduated, was forced to reflect on his life and his purpose. It was during this period of solitude, Muir says, that he determined “to be true to himself” and follow his dream of studying plants, immersing himself in nature and the outdoors. “This affliction has driven me to the sweet fields,” Muir later wrote. “God has to nearly kill us sometimes, to teach us lessons.”

Today, many of us find ourselves confined to our “darkened rooms,” or perhaps more precisely, as in Dante’s Inferno, trapped “in a dark wood, where the direct way [is] lost.” Dante goes on to tell us: “It is a hard thing to speak of, how wild, harsh and impenetrable that wood was, so that thinking of it recreates the fear.” His words speak to us over the centuries. Dante had Virgil to lead him out of the gloom. Who will be our guide?

When I really need to escape, I paddle my canoe over to an island in the lower Connecticut River—a rocky, wooded, wild place with a meandering creek and marshes on the back side. The day I visited, I beached my craft near the inlet on the northern end, following a trail into the woods up to the crest of a ridge, a couple of hundred feet above the river. Seated on a rock in a clearing, I looked down through the dark trees to the glittering water. It was late afternoon, when the sounds of the powerboats fade away and a deep solitude washes over the place. The stillness was a tonic.

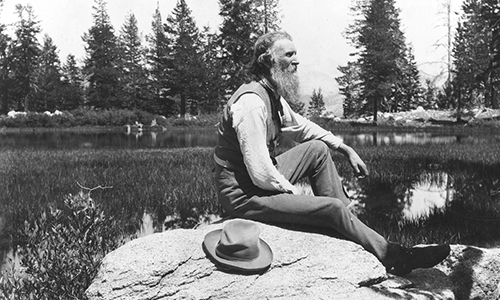

John Muir, ca. 1902

Image Credit: Library of Congress

In that ethereal quiet it was hard to image that in the 19th century this island swarmed with 600 men, mainly Irish and Italian immigrants, who lived in camps from May to October to work the granite quarries. It was an extensive operation, with steam drills and derricks and a narrow gauge railroad to haul the massive blocks to waiting schooners. This island in the Connecticut River was known for its usually dense gneiss, prized in New York City and Philadelphia for street paving and curbing.

Quarrying ended abruptly in 1902, when the stone business was no longer profitable. The woods grew back, and the island became a haven for those who wanted to escape, for whatever reason. In the 1930s, a reputed gangster hid out on the island to evade capture. He built a lean-to against some rocks and camouflaged it with branches. Friends brought him food and supplies. The authorities never found him.

The island’s best-known hermit was a fellow by the name of Andrew Holloway. Jilted by his wife who favored his brother, Holloway vowed never to speak to another human being. He built a houseboat and paddled it to the island, where he lived as a recluse for 50 years. When friends came to visit, he communicated by writing on a slate.

A beautiful, wild, lonely place, this island.

–Erik Hesselberg, Managing Editor