By Bill Hobbs

“I'm not a criminal,”

“I'm not a criminal,”

said Paddington.

“I'm a bear!”― Michael Bond, A Bear Called Paddington

As black bear populations continue to grow in the Connecticut River Valley and beyond, now more than ever there’s a need for people and public officials to work together to sustain a healthy bear population.

The road to coexistence with black bears, however, is not an easy one. Ask residents in wildlife areas who have lived near cougars or wolves and they’ll tell you how difficult it can be.

Connecticut has the smallest black bear population in New England—about 800. Yet, the state has among the fastest growing populations, increasing 10–15 percent per year. “Their geographic range is expanding and so hasn’t our involvement,” explained Paul Rego, wildlife biologist for Connecticut’s Department of Energy and Environmental Protection. “Our biggest concern [now] is bear conflict,” said Rego.

In 2019, Rego said black bears broke into 20 or more Connecticut homes. If a bear damages fruit trees, crops, livestock, or personal property, Rego said officials will trap the offending bear, ear tag it for monitoring purposes, and put the animal through a negative experience like using loud noises, before releasing it back into the wild.

The practice is called “aversive conditioning” and is designed to modify the bear’s behavior and teach it to avoid specific places. The practice has mixed results. Rego said offending bears are rarely relocated. The reason why is because bears have a “very strong homing instinct,” often returning to the same spot. Further, the department can’t move bears out of the state because no state will allow it.

Rego’s colleagues in New Hampshire, Vermont, and Massachusetts, other states that border the Connecticut River Valley, face similar challenges.

“Educating the public on bear-human conflicts is a significant priority for our department, and we spend substantial time on it” distributing brochures, giving lectures, broadcasting radio announcements, and issuing press releases, said Andrew Timmins, bear project leader for New Hampshire’s Fish and Game Department.

Timmins said New Hampshire, a state that flanks the Connecticut River for over 140 miles, has a bear population of 5,600, one of the largest in New England, growing at two percent per year. Elsewhere, Forrest Hammond, black bear project leader for Vermont’s Fish and Wildlife Department, said game wardens and his staff field “daily inquiries” from the public about how to deal with bears. In addition, Dave Wattles, black bear and furbearer biologist for the Massachusetts Division of Fisheries and Wildlife, said his office tries to “educate the public to change their behavior” and do simple things like secure their garbage.

“Bears aren’t going to change,” Wattles said. “They’re driven by food.”

So, what can the public do to help mitigate bear-human conflicts?

In short, have an offense and be responsible if you have bears in your area, officials urge. Take down your bird feeders if bears have robbed them and keep them down. Don’t throw food scraps in your compost heap, and consider putting electric fences up around chicken coops and beehives, if you own them. “Bears learn that chickens and beehives are easy meals,” Wattles said.

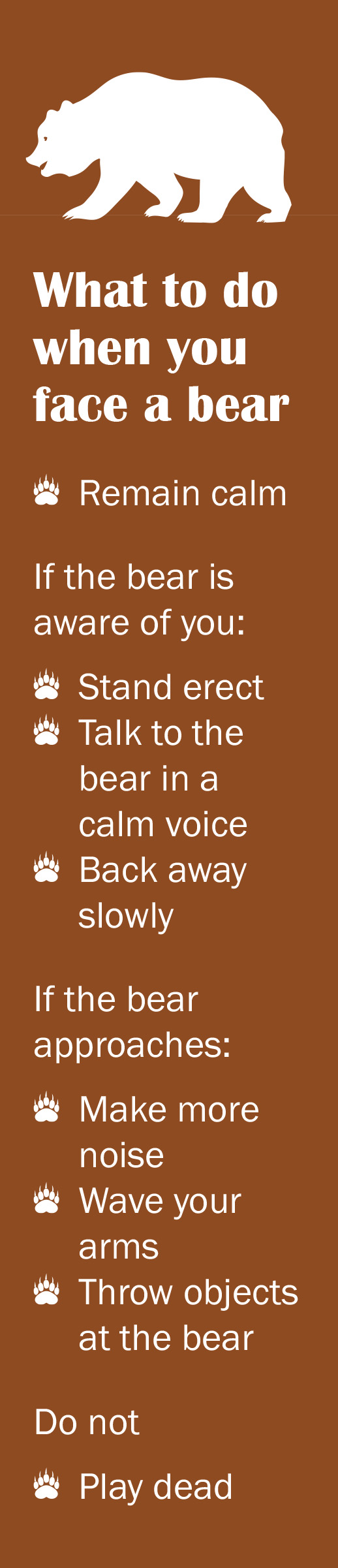

Finally, what should you do if you encounter a black bear? Though it may be almost impossible to do, remain calm.

If the bear is aware of you and does not flee, experts urge you to stand erect and talk to the bear in a calm voice and back away slowly. They also caution you to never run or climb a tree. Why? Black bears can sprint up to 35 miles per hour and are excellent tree climbers.

“If the bear approaches, be offensive. Make more noise, wave your arms, and throw objects at the bear,” the Connecticut Department of Energy and Environmental Protection website advises. “Black bears rarely attack humans. But, if you are attacked, do not play dead. Fight back with anything available.”

While our state officials are doing their level best to manage a growing black bear population, we need to do our share, and be mindful of these big animals, and do easy things like securing all potential food sources and keeping our pets inside at night.

“In my mind, their loss would be a terrible thing if we didn’t learn to live together,” said Wattles.

Bill Hobbs is a nature columnist for The Day in New London, CT. He is a resident of Stonington and lifelong wildlife enthusiast. For comments, he can be reached at whobbs246@gmail.com.

Getty Images, twigymuleford