By Erik Hesselberg

Artwork and objects courtesy of the Connecticut River Museum. Shad Shack painting by Janette Boothby. Photography by Jody Dole. Shad Drawing from Getty Images, gyro

On a fly by day or a gill net by night, when the shad run, we fish!

Early on an April morning, a cold mist lies over the Connecticut River. When the sun breaks through and the mist rises, there is shimmering on the water. Regularly, for a brief moment, the modern melds into the timeless and across the expanse of marshes and blue water you see the silver flash and hear the blare of a diesel horn from the Old Lyme Draw every time an Amtrak train speeds along the old truss railroad bridge. You imagine some of the busy commuters on their way between Boston and New York looking up from their laptops to refresh themselves with a view of the tidal creeks and coves and the wide River meeting the waters of Long Island Sound beyond. The sleeping yachts are still wrapped in their white plastic cocoons for the winter. Marking the shore in the distance stands Lynde Point Lighthouse, and beyond, Saybrook Outer Light.

The brackish water of the wide estuary is warming past 40 degrees Fahrenheit. In front yards, yellow forsythia has appeared, and clusters of yellow daffodils push up. The season has begun, and the shad are running. Where marsh becomes damp woods, you can still see here and there among the bare branches the fresh white blossoms of a small tree above the fiddlehead ferns and green shoots of skunk cabbage. This is a species of Amelanchier, the shadbush, given this homely name by the early English settlers because it flowers about the same time huge schools of shad return from the ocean and swim up New England tidal rivers.

The brackish water of the wide estuary is warming past 40 degrees Fahrenheit. In front yards, yellow forsythia has appeared, and clusters of yellow daffodils push up. The season has begun, and the shad are running. Where marsh becomes damp woods, you can still see here and there among the bare branches the fresh white blossoms of a small tree above the fiddlehead ferns and green shoots of skunk cabbage. This is a species of Amelanchier, the shadbush, given this homely name by the early English settlers because it flowers about the same time huge schools of shad return from the ocean and swim up New England tidal rivers.

A dirt road full of potholes leads down by an abandoned power station to an old stone wharf with weathered wooded slips along one side. Pow erboats are predominant, but once at Ferry Dock, as this wharf is known, you see the remnants of a fishing fleet—a 40-foot trawler, a few lobster boats, and several flat-bottomed, open skiffs about 20 feet long. Back from the water among the fishermen’s cottages is Ted’s Bait Shop, owned by Ted Lemelin, who used to take one of the long skiffs out at night to set his drift nets for the spring shad fishing. Ted is a hard guy to know, but one night in May, he agreed to take me out fishing with him.

erboats are predominant, but once at Ferry Dock, as this wharf is known, you see the remnants of a fishing fleet—a 40-foot trawler, a few lobster boats, and several flat-bottomed, open skiffs about 20 feet long. Back from the water among the fishermen’s cottages is Ted’s Bait Shop, owned by Ted Lemelin, who used to take one of the long skiffs out at night to set his drift nets for the spring shad fishing. Ted is a hard guy to know, but one night in May, he agreed to take me out fishing with him.

There has been shad fishing on the Connecticut River—more or less this kind of laying out of carefully arrange weirs or barriers—for thousands of years. River Indians called the first full moon in March the Shad Moon. (Today, on the Connecticut River shad season runs from April 1 to June 15.) Taking his cue from Native belief, Connecticut poet John G.C. Brainard in 1824 wrote “The Shad Spirit,” telling of a spirit guide in the form of a great bird who appeared in early spring to lead the fish schools up the coast to the mouth of the Connecticut River:

To fair Connecticut’s northernmost source,

O’er sand-bars rapids and falls,

The Shad Spirit holds its onward course,

With the flocks with his whistle calls.

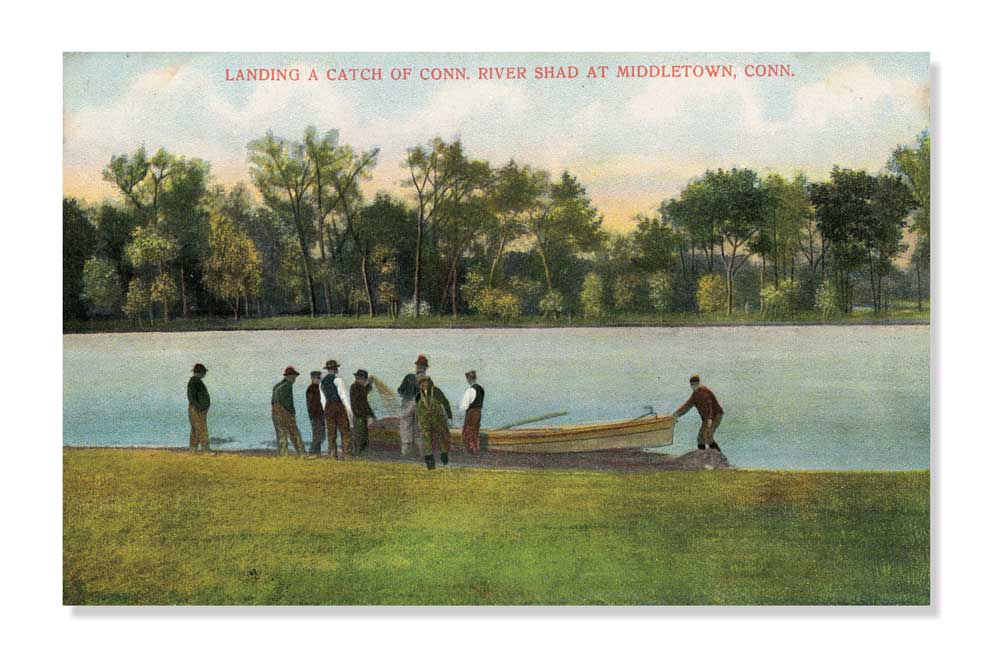

The broad estuary between Saybrook and Old Lyme bristled with fishing piers. From the piers haul-seining crews worked nets a quarter mile long. A thousand or even two thousand fish in a single sweep of the net was not uncommon. Shad was so plentiful it was used as fertilizer or shipped to the slave-worked sugar plantations of the Caribbean. However, with the steamboat the fresh catch could be packed on ice and sent overnight to New York and Boston. The humble fish began to rise in estimation, and soon Connecticut River shad and shad roe graced the tables of flossy restaurants like New York’s Delmonico’s.

A planked shad dinner is still a seasonal treat, although the market for the fish has dwindled, as an older generation raised with shad bakes and the like slowly disappears. Today, only a handful of boats go out at night to lay drift nets for shad, classified as an “artisanal fishery” fading into folklore. In 10 years, the gillnet shad fishery will have likely disappeared altogether. “It’s hard work and you fish at night, so you’re going without sleep for the five- or six-week season,” a fisheries biologist told me. “The gear hasn’t changed in 100 years. Only a few diehards do it now.”

Some years ago at Ferry Dock, I met Reginald “Butch” Rutty, a commercial fisherman for 40 years. Rutty talked about the days when 20 boats raced out to the Railroad Bridge at night during shad season to be the first on the fishing grounds. The bridge marked the top of the “reach,” the territories of water allotted to fishermen over generations to lay their nets. “The first boat on berth earned the right to the first drift,” Rutty said. “You’d anchor your boat on the south side of the bridge to establish your spot. Some guys got out there early, which was O.K. as long you left your net in the boat.”

Some years ago at Ferry Dock, I met Reginald “Butch” Rutty, a commercial fisherman for 40 years. Rutty talked about the days when 20 boats raced out to the Railroad Bridge at night during shad season to be the first on the fishing grounds. The bridge marked the top of the “reach,” the territories of water allotted to fishermen over generations to lay their nets. “The first boat on berth earned the right to the first drift,” Rutty said. “You’d anchor your boat on the south side of the bridge to establish your spot. Some guys got out there early, which was O.K. as long you left your net in the boat.”

Rutty got his start fishing with Kenny Swain, a hardnosed commercial fisherman out of Old Saybrook who described his line of work as “a tough racket.” Rutty signed on as Swain’s “striker,” or junior partner, but a few weeks in, may have questioned the decision when their 35-foot fishing boat was broadsided by a 54-foot cabin cruiser, nearly slicing it in two. Swain and Rutty were thrown into the water but were plucked up by a passing vessel. Both were bruised and battered but refused medical attention and were back fishing the next day.

Kenny Swain fished right to the end. They still talk about the bitter cold January morning in 1980, when Swain collapsed on his boat on Long Island Sound. A passing boat spotted the distressed vessel, but it was too late. Swain’s death was a blow to the tight-knit Old Saybrook fishing community, especially Lemelin, who also got his start fishing with Swain. Indeed, much of what he knew about shad, he said he learned from Swain.

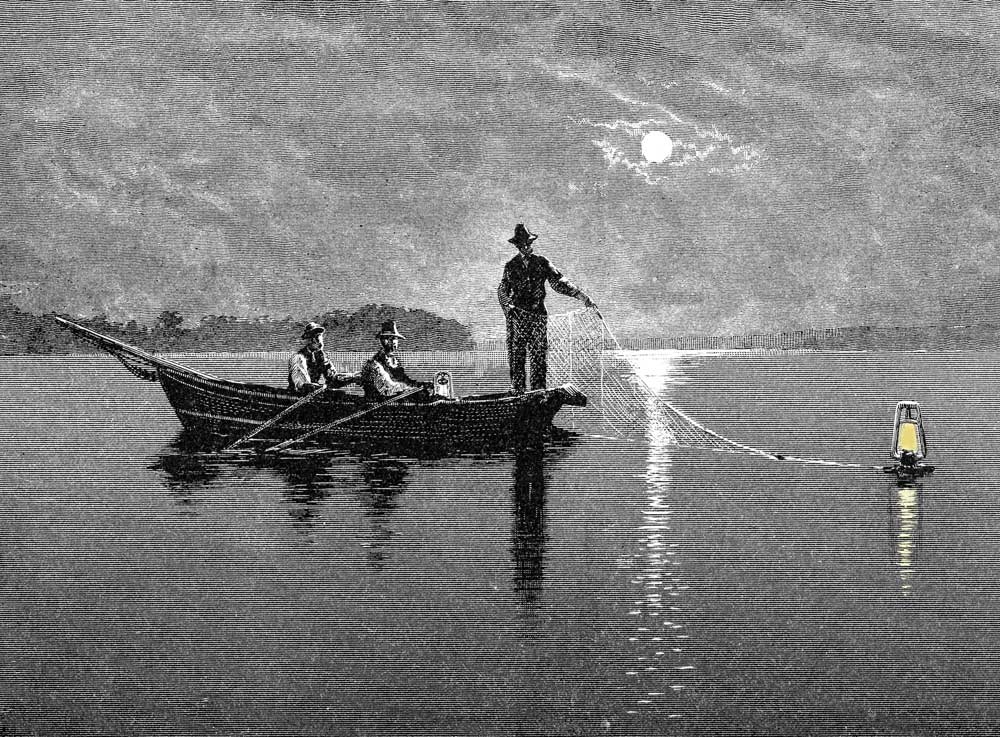

There was fog in the evening. The next day, Ted called to say the weather would be clear and he was fishing that night if I wanted to tag along. It was long after midnight when we pushed off from the dock and headed out into the blackness of the Connecticut River. John Rogers, Ted’s fishing partner, was in the bow. Approaching a red buoy, Ted cut the motor. With his free hand he directed a floodlight onto the downstream side of the buoy—No. 14, marking the eastern edge of the dredged channel. Shad gill-netters typically fish an ebbtide, letting the net drift down with the current a mile or so before taking it up. You don’t want it to move too fast. “I don’t know, Johnny,” he said to Rogers. “The current’s still running pretty good.” When shad, a schooling ocean fish, come into the River to spawn, they follow the deep channels. Approximately half a million fish would head upriver that year, which meant a half million fish would pass Red Buoy No. 14. Ted would be happy to intercept 150 of these fish, but his success tonight seemed to depend on how well he read the eddy coming off the buoy. “I don’t want the current to take my net down too fast and get all hung up in South Cove,” Ted said. “It’s kind of a crap shoot.”

Leaning on the throttle, Ted cruised upriver to a spot just south of the railroad bridge where he would make his set. He and John wear the uniform of commercial fishermen everywhere—flame-orange, rubberized bib overalls and wool caps. They are heavily bearded. Working in tandem, they began paying out 1,500 feet of net across the channel in a long, lazy arc. Shad have a remarkable ability to detect and avoid nets. But they can’t see them at night. Swimming into the nylon monofilament, the fish are caught at the gills.

These gill nets have 5 1/2-inch meshes which select for the coveted female roe shad. (Males are called bucks.) Ted’s net is 15 feet deep, about the depth of the channel, held down in the water by metal rings and buoyed by plastic floats, still called “corks” from the old days. The rings tear off if the net gets hung up on the bottom. Battery operated lights mark the ends, a rare concession to modern technology. One is blue, blinking—a signal to other boaters to stay clear. Ted and John would let the net drift down with the current about a mile before taking it up, just above South Cove. If they’re lucky, they would catch some fish.

Between us and the bridge we saw the lights of a fishing boat. “That’s Gary,” Ted said, referring to Gary Rutty, Butch Rutty’s brother. Amos Swain and his crew were also out tonight. Ted shook his head. “Three boats! Hell, I remember when you had to fight for your spot there were so many shad boats on the water. One guy would set, then another and another right on down the line. If you didn’t set in time, you’d lose your spot. There were fistfights back at the dock.”

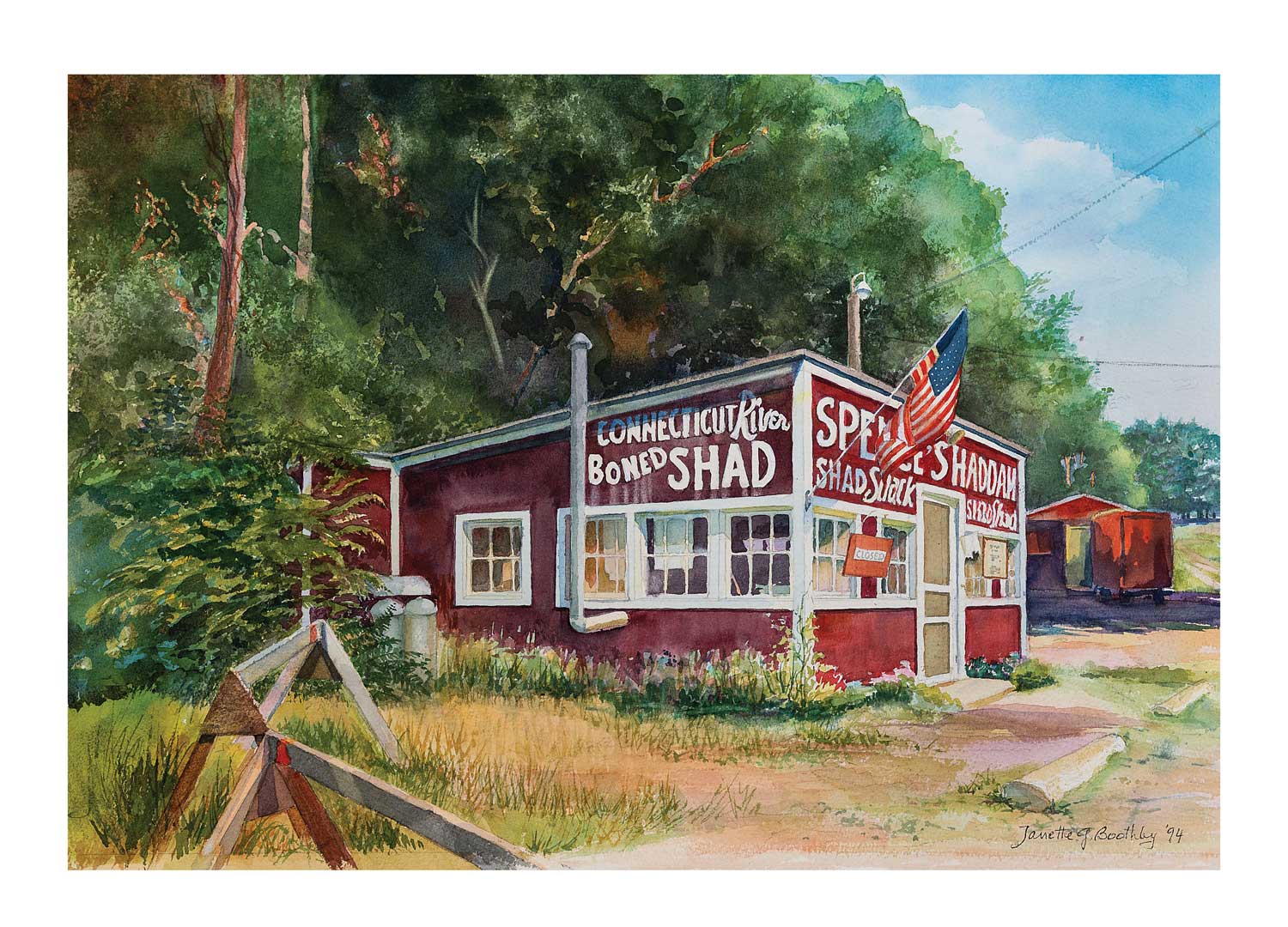

Originally from Bath, Maine, Ted came to Old Saybrook in the 1970s. Shad fishing was booming. “I had 12 people working for me,” he said. “Sometimes, we boned 1,000 fish a day. Dock & Dine was buying 200 pounds of fish a week. It was good money. You could clear $5,000 even $10,000, in just five or six weeks. Today, kids don’t even know what a shad is. All my customers are old. When they come to pick up their fish, I’ve got to bring it over to them because they can’t walk.”

Originally from Bath, Maine, Ted came to Old Saybrook in the 1970s. Shad fishing was booming. “I had 12 people working for me,” he said. “Sometimes, we boned 1,000 fish a day. Dock & Dine was buying 200 pounds of fish a week. It was good money. You could clear $5,000 even $10,000, in just five or six weeks. Today, kids don’t even know what a shad is. All my customers are old. When they come to pick up their fish, I’ve got to bring it over to them because they can’t walk.”

At 3 a.m. on the Connecticut River, the air is cool, damp, and salty-tanged. Mist rises from black, glassy water. The long, low silhouette of Great Island stretches away to Long Island Sound. Off in the distance, Lynde Point Light winks on, then off. Ted shined his floodlight along the length of his net. It was lying diagonally across the channel.

“She’s sagging and I ain’t bragging,” Rogers said, referring to the belly in the —not an encouraging sign. “We’ll be lucky if we catch 10 fish,” Ted grumbled.

“She’s sagging and I ain’t bragging,” Rogers said, referring to the belly in the —not an encouraging sign. “We’ll be lucky if we catch 10 fish,” Ted grumbled.

The two fishermen start hauling. The first 50 feet contain only stripers, the bane of the shad fishermen, as they eat shad. They also foul your nets. Commercial striped bass fishing is banned, so this bycatch goes over the side. Finally, a shad. Then two, three. Ensnared in the net, the fish barely twitch. Ted and John extract the gilled fish by gripping them tightly between their knees and forcing their heads through the tight meshes. The shad are tossed into a plastic tub in the stern. More net, more shad. The tub is filling up. By the time all 1,500 feet of net is in the boat, 40 shad lie in the tub, their big silvery scales shimmering under glaring lights.

Ted would go broke if he had to rely just on shad fishing for his income. His real work is running his bait shop and a car-towing business. Ted was discouraged when his son didn’t want to carry on the tradition. “The other day I asked him what wanted to do when he was older,” Ted said. “You know what he said? ‘Dad, I can tell you what I’m not going to do. I’m not going to be a fisherman.’”

Two hours on the River and all Ted has to show for it is 40 fish. Still, there are other compensations. Few places are as peaceful as the Connecticut this May night. At 3 a.m., Ted and John own the River. Looking down at hiscatch, Ted says, “I don’t know John. It ain’t great. But it ain’t bad. I think we’ll make another drift.”

Erik Hesselberg has been writing about the Connecticut River for twenty years, first as an environmental reporter for the Middletown Press, and then as executive editor of Shore Line Newspapers in Guilford, where he oversaw twenty newspapers. He lives in Haddam, Connecticut, where he is at work on a book about Connecticut River steamboats. A portion of this story previously appeared in the New Haven Register in a slightly different form.