The Connecticut- Meet the River

By Sydney M. Williams

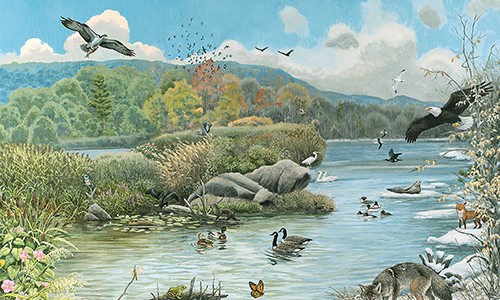

“Seasonal Ecology Mural” by Mike di Giorgio. Courtesy of Connecticut River Museum. Photo by Cultural Preservation Technologies.

“This river, what is it called?”

Balty asked the ferryman.

...

“A Hollander’ll tell you this is the Fresh River. But you won’t be finding many Hollanders hereabouts anymore. We calls it the Great River. Which it be.”

Christopher Buckley (1952–)

The Judge Hunter, 2018

(story takes place in 1664)

The word “Connecticut” stems from a French corruption of the Mohegan word “Quinetucket,” which means “beside the long tidal river.” Adriaen Block, the Dutch explorer and first European to chart the River in 1614, called it the Fresh River. The English first settled the area in the 1630s and referred to it as the Great River. During the next couple of decades, the English moved west from the Massachusetts Bay Colony and north up the River, forcing the Dutch to retreat westward to New Haven, which was settled in the 1640s. By 1654, the English–Dutch boundary was established near what is now Greenwich, separating the Connecticut Colony from the New Netherland Colony (New York). During those years, the Great River began to be called the Connecticut, as was the colony established along its banks.

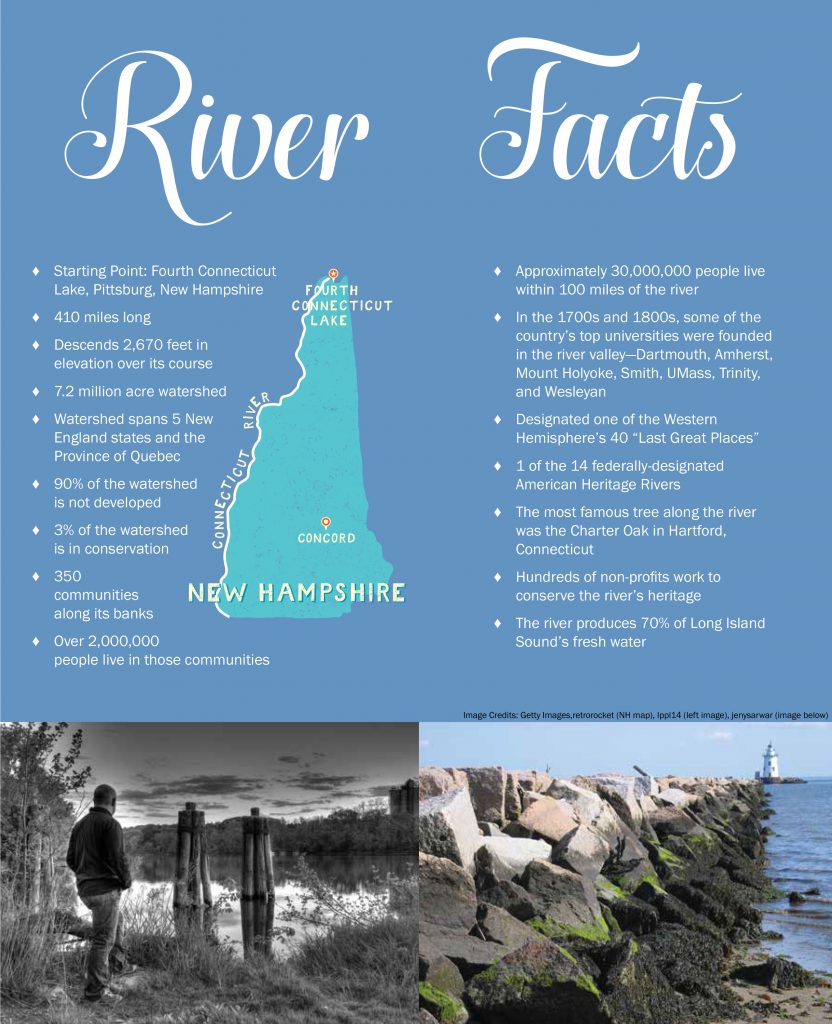

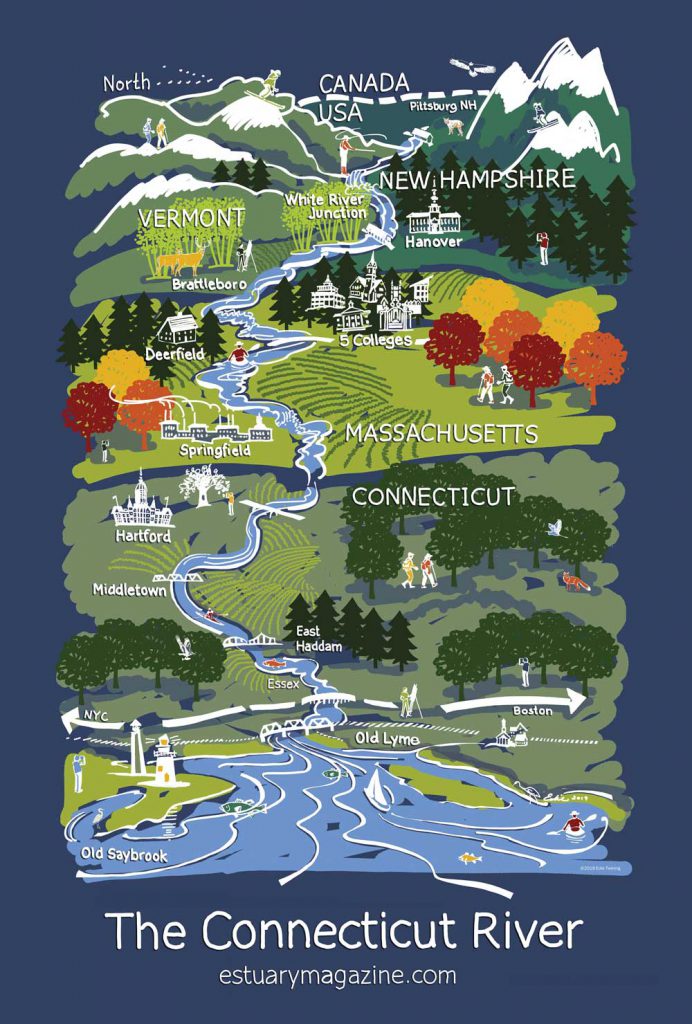

The Connecticut River begins its 410-mile trip to the sea in Pittsburg, New Hampshire. The iconic town was described by David Duncan in a 1985 piece for the New York Times: “Pittsburg (current population 832) is a lazy village that in 1832 was the capital of a short-lived nation, the Indian Stream Republic, which drew up its own constitution and elected a president during border disputes between Canada and New Hampshire.” The River has its origin in the Fourth Connecticut Lake, just above Moose Head Dam and about 300 yards from the Canada–US border, a boundary fixed by the 1783 Treaty of Paris that ended the Revolutionary War. Over its long run to the sea, the River descends 2,670 feet, with a watershed that spans five of the New England states (Maine, briefly) and the Province of Quebec. The watershed encompasses 7.2 million acres (twice the size of the State of Connecticut) and includes one hundred and forty-eight tributaries, on which once sat 3,000 dams and over which there were 44,000 crossings. Ninety percent of its watershed is undeveloped, with only 200,000 acres (3 percent) in conservation. Over two million people live in the 350 communities along its banks. The Connecticut begins its journey in a southwesterly direction before hitting the New Hampshire–Vermont border, then heads pretty much due south, until the “big bend” just south of Middletown, Connecticut, where it flows southeasterly until it reaches Long Island Sound between the towns of Old Saybrook and Old Lyme. As the River enters Long Island Sound, 19,600 feet of water are discharged per second, producing 70 percent of Long Island Sound’s fresh water.

What we now know as the Connecticut River valley was formed as glaciers that covered most of New England receded north about 12,000 years ago. Lake Hitchcock, one of the largest glacial lakes in North America, extended from Middletown, Connecticut, to Bath, New Hampshire, a distance of 210 miles—a lake slightly larger than Lake Huron. More than half of today’s River lies within that basin. Man began to inhabit the fertile ground around the River, left behind by the retreating glacier. Artifacts near the town of Gill, Massachusetts, (near Northfield) and East Windsor, Connecticut, show the presence of man from between five and eight thousand years ago. Rock engravings found in Bellows Falls, Vermont, and Claremont, New Hampshire, date the presence of Native Americans to 800 AD. The soil was rich, the woods burgeoned with game, and the River, filled with fish, served as a highway for these mostly nomadic tribes.

It was that richness of the region, made accessible and commercially viable by the River, which attracted settlers. Shipping cargo by water has long had economic advantages over moving goods by land. In a recent interview, the economist Thomas Sowell was quoted: “If you are born up in the mountains and someone else is born in the river valley, then the odds are huge against you of ever being as prosperous as the person born near the river.” But, for commercially focused European settlers, the Connecticut River had to be navigable from its source near the Canadian border to its confluence with the sea. Problems to overcome included rapids, such as the falls in Windsor, Connecticut; Turners Falls in South Hadley, Massachusetts; and a number of falls in the Vermont towns of Barnet, Wilder, Hartland, Bellows Falls, and White River Junction. Between 1791 and 1828, a series of transport canals were chartered and constructed, the first being in South Hadley and the last in what is now Windsor Locks, Connecticut. The canals facilitated river traffic, and by 1848, investors commandeered enough water power to operate 450 mills. In Holyoke, where there were no rapids, a dam was constructed to divert water into canals for industrial purposes. In those early-industrial days, we were, economically, a “third-world” country, where concern for commerce took precedence over care for the environment.

But, as we grew wealthier, attitudes began to change, albeit slowly. There remain more than a thousand active and remnant dams in the four-state Connecticut River watershed, but only fifteen— including two that are breached—on the Connecticut. Four of those are in Pittsburg, New Hampshire, including the Murphy Dam, which is 106 feet high. Eight of the dams are used to produce electricity. While commerce on the River served to transform an agrarian society into an industrial one, the environmental damage done was not addressed until the 1950s, beginning with the construction of fish ladders that allowed some species to bypass dams. Keep in mind, it is not just anadromous fish that migrate upstream to spawn, all species of trout and several species of bass migrate from the Connecticut to smaller tributaries to find the right habitat for successful spawning. Besides blocking their passage, another problem that dams cause for fish is that the water temperature behind the barrier is warmer than

the running water of the River. As temperatures rise, the level of dissolved oxygen declines, damaging many species. Consequently, over the past decade, hundreds of dams in the watershed have been removed. Communities have found, according to David L. Deen, former River Steward for the Connecticut River Watershed Council, that the removal of old dams actually eases flooding conditions, especially during melting ice season, because the River flows more naturally. Dams served a purpose in the industrialization of our nation, but their societal usefulness has declined. Risks of failing, old dams and the damage any dam does to the riverine ecosystem argues that removing them is often the best and safest option.

The wealth of the area, its natural beauty, and its proximity to major urban areas (approximately thirty million people live within 100 miles of the river) have attracted artists, writers, and musicians. The Cornish Art Colony, in Cornish, New Hampshire, was established in 1895, centered around the sculptor Augustus Saint- Gaudens. It is now the Saint-Gaudens National Historic Site, but in its prime it was visited by artists like George de Forest Brush, Maxfield Parrish, and Frederick Remington. The Old Lyme Art Colony (Connecticut) was established in 1899 by Henry Ward Ranger and was instrumental in the development of American Impressionists. Artists like Willard Metcalf, Guy C. Wiggins, and Childe Hassam spent time there. Today, the Florence Griswold Museum has recreated the house and the grounds these artists once roamed. From the Marlboro (Vermont) Music Festival to Musical Masterworks in Old Lyme, music has been important to the area. Mark Twain, Harriet Beecher Stowe, and Edith Wharton all lived or spent time at Nook Farm in Hartford. Between 1769 and 1871, some of the country’s top universities were founded in the River valley: Dartmouth, Amherst, Mount Holyoke, Smith, U Mass, Trinity, and Wesleyan. Boarding schools, like Deerfield, Mount Hermon, and Loomis Chafee line its shore.

Once described as America’s “best landscaped sewer,” much has changed. In 1972, passage of the Clean Water Act regulated the discharge of pollutants into navigable waters. The Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge Act was passed in 1991, which resulted in the establishment of the Silvio O. Conte National Fish and Wildlife Refuge in 1997, to “conserve, protect, and enhance the abundance and diversity of native plant, fish, and wildlife species and the ecosystems on which they depend throughout the Connecticut River watershed.” In 1993, the Connecticut River was designated as one of the Western Hemisphere’s forty “last great places.” Four years later, in 1997, it was listed as one of fourteen Federally-designated American Heritage Rivers, and in 2012, it was named a National Blueway by America’s Great Outdoors Initiative. Today, with a focus on environmental education, habitat conservation, and the management of public and private lands, the Conte Refuge encompasses 36,000 acres in New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts, and Connecticut. Thousands of additional acres, along the River and in the watershed, have been preserved in all four states. The Roger Tory Peterson Estuary Center, a division of the Connecticut Audubon Society, has recently acquired property on the River in Old Lyme. And just this year, the estuary of the River was nominated as the site for a National Estuarine Research Reserve (NERR) by the National Oceanic Atmospheric Administration (NOAA), a division of the United States Department of Commerce. The River is now home to dozens of fish species. Just to name a few, the upper Connecticut holds Brook, Brown, and Rainbow Trout and Landlocked Salmon, while the lower part of the River is home to Striped Bass, Sea Lampreys, Shad, and Shortnose Sturgeon. Twelve varieties of mussels can be found in the River. Deer, Black Bear, Fox, Coyotes, and Bobcats roam its banks, while Muskrats, Beavers, and Otters make their living in its waters. Hundreds of native and migratory birds, from Partridges, Bald Eagles, Great Horned Owls, Osprey, and Sea Gulls to Saltmarsh Sparrows, Sand Pipers, American Black Ducks, and Tree Swallows call the River and its marshes home, at least for a few weeks. Dozens of tree species line its banks, from Northern Spruce, Red and Sugar Maples to Oak and Hickory. The most famous tree along the River is (or was) the “Charter Oak” in Hartford. In 1662, Charles II had granted the Connecticut Colony an unusual degree of autonomy. Twenty-five years later, in 1687, his successor James II demanded the Charter back. But instead of returning it, the Charter was hidden in a large White Oak on the property of Wyllys Hyll. That act of defiance is still remembered, and the State of Connecticut is known today as the Charter Oak State.

Windmill on the banks of the Connecticut River in Essex, CT

Image Credit: Getty Images

The commercial history of the Connecticut River is multi-industrial. The River served as a highway, first for Native Americans and later for explorers, trappers, and fishermen. As settlers started farms and formed villages and towns, the River became the principal means for transporting farm produce and industrial goods—tobacco from flatlands in Connecticut, corn and wheat from fields in Massachusetts, dairy products from Vermont, lumber from New Hampshire, and apples and pears from all four states. Merchants traded with the West Indies and fed coastal cities with produce and meat. Great slabs of Vermont marble, Connecticut brownstone, and New Hampshire granite were carried down the River and became building materials in Boston, New York, and Washington. Shipbuilders in Connecticut towns of Glastonbury, Portland, and Essex were world renowned, building more than four thousand ships in the 19th century. Cities, like Hartford, Springfield, and Brattleboro sprouted along its shore, built around saw mills, leather factories, and grain mills. Ivory was imported from Africa for the manufacture of piano keys, buttons, and combs, and nutmeg from Indonesia was used in desserts and in drinks like eggnog and mulled wine, which gave Connecticut a second nickname.

In early years, war along the River was pretty much a constant. Native American tribes fought one another and allied with either the French or the English, depending on which was in their best interest. Settlements along the River were suspended in the northern territories during King Phillip’s, or Metacomet’s, War (1675–1678), causing the abandonment of settlements in Deerfield and Northfield for a generation. Twenty-six years later, when settlers had returned, during Queen Anne’s War (1702– 1713), the famous raid on Deerfield took place in 1704. The town was attacked by French soldiers and Native Americans from the Abenaki and Pocumtuc tribes, all under the command of Jean-Baptiste Hertel de Rouville. Fifty-six villagers were killed, with a hundred taken to Canada as hostages or prisoners. Two years later, sixty were returned. Settlements along the lower part of the River were affected by the French and Indian War (1754–1763). Two unintended consequences of that war were that it served to unite the colonies against a common enemy, and it allowed the colonists to view their soldiers as a volunteer militia rather than a standing army, which would serve them well thirteen years later.

Ct. River Map by Edie Twining.

“ I choose to listen to the river for a while,

thinking river thoughts, before joining the night and the stars.”

The River played other roles in our nation’s wars. Connecticut was largely unaffected by battles during the Revolutionary War, but the fertile River valley, along with saltworks in East Haven and ironworks in Salisbury allowed it to be a provider of necessities for an army. General George Washington referred to Connecticut as “the provision state,” for its beef, salt, flour, and gunpowder, much of which was delivered via the River. In South Glastonbury, alongside the Connecticut River, the Stocking family owned one of New England’s four gunpowder factories. Despite an explosion in 1777 that killed her husband, Eunice Stocking continued to produce gunpowder for the army until the war’s end in 1783. On June 13, 1776, the warship Oliver Cromwell, the first warship of the Revolution and built by Uriah Hayden, was launched in Essex. The ship seized nine British frigates before being captured by three British ships and renamed HMS Restoration in June 1779. Also built in Essex was the world’s first submersible craft, the Turtle, launched in November 1776 and built by David Bushnell.

During the War of 1812, the British blockaded Long Island Sound, essentially shutting down trade and commerce vital to Connecticut’s well-being. And then, on an April night in 1814, a British raiding force rowed the six miles up the River to Pettipaug (now called Essex) where they torched twenty-seven ships—the greatest naval loss during the war—and the greatest US Naval loss until Pearl Harbor. Gideon Welles of Glastonbury, scion of a shipbuilding family, became Abraham Lincoln’s Naval Secretary. He expanded the US Navy by ten-fold during his tenure. The Gildersleeve boat works in Portland produced the steam-powered gunboat the Cayuga in 1861 and the United States in 1864, the largest steamship in the country, with a gross register tonnage of 1,289. (She was lost off Cape Romain, South Carolina, in 1881.) During the Civil War, the River served as the means of transporting weapon-making machinery from Pratt and Whitney, engines from Woodruff and Beach in Hartford, and weapons from Colt, also in Hartford. The motor patrol boat, USS Dauntless was built in Essex in 1917 as a private motor boat and then leased by the US Navy during World War I.

On his renowned flight to Paris in May 1927, Charles Lindbergh flew over the mouth of the River. In his 1953 book, The Spirit of St. Louis, Lindbergh wrote of the experience: “As I approach shore, near the Connecticut River’s mouth, wing tips tremble again. For some reason it bothers me less than before. Possibly the air isn’t as rough. Possibly I feel that the structure passed its crucial test over Long Island. It may be my knowledge that the plane is already a few pounds lighter; or simply optimism springing from a successful start. At any rate, the bumps no longer cause an ache in my armpits.” The Connecticut River, its history and magnitude, has earned our respect and deserves our support. That can be as simple as picking up someone else’s litter or not stepping on a budding Jack-in-the-Pulpit, or it can be as complex as negotiating a land deal to acquire more open space or constructing ladders for spawning fish. Because of abundant natural resources, such as the Connecticut provides, and an ethic that reveres hard work, we have become, as a nation, wealthy. Americans are a generous people who give back a larger percentage of income and wealth than any other people. The River has long had a need for conservation. In an 1819 publication of A Statistical Account of Middlesex County, the author wrote regarding the Connecticut River: “For several years, the quantity of fish in the river has very considerably decreased.” Overfishing, raw sewage, residue from tanneries and a lead mine were all, in part, responsible. The Industrial Revolution was in its infancy, and the River became more polluted as living standards were deemed more important than the environment. But, as wealth came, attitudes changed, and the River has become cleaner and the environment purer. Today, there are hundreds of non-profits the length of the River helping to conserve its heritage. Is there more to be done? Certainly, but consider where we are today versus a hundred years ago, versus fifty years ago, and twenty years ago.

Those of us who live in towns along this “long tidal river,” whether in New Hampshire, Vermont, Massachusetts or Connecticut have in common this “great river.” In 1806, Yale President Timothy Dwight visited the Connecticut River Valley on horseback. He wrote: “The inhabitants of this valley…possess a common character, and, in all the different states, resemble each other more than their fellow citizens who live on the coasts resemble them.” The River is part of our lives. We drive over it on super highways and cross over it by covered bridges. We take ferries. We use it for sports, kayaking in its northern parts and in saltwater marshes near its mouth. Scullers and oarsmen race on the River in Hanover, New Hampshire, Greenfield and Amherst, Massachusetts, and Hartford and Middletown, Connecticut. We fish its waters—fly fishing for Trout in Pittsburg, New Hampshire, and Shad fishing in Essex. We should and we must conserve what we have been gifted. But we must also recognize that part of wisdom is being adaptable— not trying to change nature’s natural forces, playing neither Devil nor God. Twenty-six years ago, the essayist and environmentalist Edward Abbey wrote: “I choose to listen to the river for a while, thinking river thoughts, before joining the night and the stars.” Good advice, as we give thanks for the Connecticut River—a repository of history, a source of beauty and delight and a treasure to be enjoyed and conserved.

Arches of Bulkeley Bridge over the Connecticut River in Hartford, CT

Image credit: Getty Images, Holcy

Sydney Williams was born in New Haven, Connecticut, and grew up in New Hampshire. Following mandatory military service, he graduated from the University of New Hampshire

and then spent 48 years on Wall Street. In early 2000, he began writing a “Market Note,” which morphed into essays on politics (“Thought of the Day”) and other subjects. He has authored three books: One Man’s Family: Growing Up in Peterborough & Other Stories, Notes from Old Lyme: Life on the Marsh & Other Essays, and Dear Mary: Letters Home from the 10th Mountain Division, 1944–1945. His next book of essays will be titled, Essays from Essex, with a subtitle yet to be determined. Williams has been married to his wife Caroline for 55 years; they have three children and ten grandchildren, and live in Essex, CT.

Edie Twining has been a designer for over thirty years. After graduating from the School of the Boston Museum of Fine Arts, she received a degree in interior design from Wentworth Institute of Technology. Edie has worked as a graphic designer, book illustrator, and commissioned artist, and works with wood, paper, and textiles. www.twiningdesign.com