It’s All About the River’s Water Quality

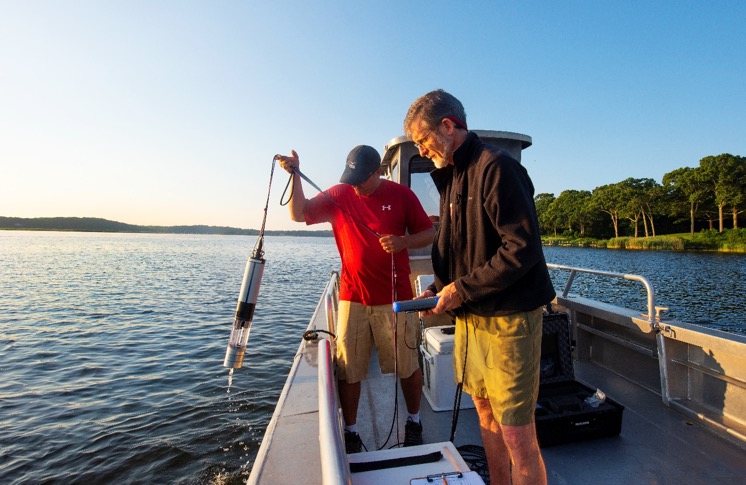

Photograph by Jody Dole

"Clean, Healthy, and Full of Life! "

That’s Andy Fisk’s goal, and not just a dream, for the Connecticut River. Fisk, a patient, persistent, articulate scientist, is executive director of the Connecticut River Conservancy, a water-shed scale conservation organization based in Greenfield, Massachusetts. He can take water samples in the morning and debate experts on water quality policy in the afternoon. Fisk is among those who comprehend the arduous journey from water testing to legislation based on those tests, with a lag time of 5, 10 or even 15 years. Good, sound, effective water policy development must therefore necessarily survive multi-generations of elected officials in governors’ mansions as well as the White House.

A brief history of the environmental movement at the federal level bears repeating. Public opinion regarding air and water pollution was largely shaped by Rachel Carson’s book, Silent Spring, published in 1962, and sensationalized catastrophes such as the 1969 fire on the Cuyahoga River in Ohio. In 1970, President Richard Nixon brought the Environmental Protection Agency into being with William Ruckleshaus as its first head. Ruckleshaus noted that, “public opinion remains absolutely essential for anything to be done onbehalf of the environment.”

The Clean Water Act of 1972 brought voluntary standards for discharges of pollutants into navigable inland waterways. President Jimmy Carter’s EPA administrator, Douglas M. Costle, who had also led the study in the late 1960s that recommended the creation of the EPA and in 1975 was Connecticut’s Commissioner of Environmental Protection, championed the Clean Water Act (as amended) of 1977. This act outlawed the use of any pipe or man-made ditch for discharges into navigable waters. The law also required industry to meet “best technological standards” for specified pollutants with a deadline for compliance of 1984. “Voluntary compliance” was replaced with “mandatory compliance with penalties.”

The die was cast. Industries, farms, and individuals made the necessary investments. The Connecticut River rose from a Class D (basically, dirty and unsanitary) River to a Class B River, which it is today. Fish and people were able to swim in their rivers once again. So, is the battle over? Is clean water here to stay? Not if one believed Ruckleshaus in 1972: “…the environment is a problem you must tend to everlastingly. It doesn’t go away. It’s not like putting out a fire or even building a highway. You can’t do it, then brush your hands and say, ‘On to the next task.’ You have to keep at it all the time; otherwise it starts to slide back.”

Sliding backwards may include acute problems such as bacteria caused by a leak or a broken pipe. Once detected today, however, such impairments are rectified and clean water is restored rather quickly.

The battle’s not over if you’re Andy Fisk, either. Fisk looks to the day when the Connecticut River is “clean, healthy, and full of life.” Just because it’s clean doesn’t mean it’s healthy, says Fisk. “Nevertheless, fish, wildlife, and plants will flourish in and along a healthy river. The goal is that decades from now, we could see the return of millions of blue-back herring, alewives, and shad.”

A river that is “clean, healthy, and full of life” would seem to be in everyone’s best interests. Fisk says work on “healthy” began 20 years ago involving matters such as storm water, nutrient control, and even the depth to which sunlight penetrates the water. The way forward is somewhat more complex, however.

The Clean Water Act has enabled the River to get to “clean” but falls short of helping to restore large populations of fish and desirable aquatic plant life. Now, says Fisk, the CWA must be married with various state wildlife conservation laws to get to “healthy.”

For the way forward, complex interdependencies become more important than simpler dependencies; dependencies such as, “the more dissolved oxygen in the water, the better it is for trout.” As an example of interdependencies, clearer water lets in more sunlight. Sunlight to greater depths allows more eelgrass to grow. Eelgrass is used by fish such as trout to spawn and is used by their young for protection. Therefore, more sunlight to greater depths is good for trout.

In addition, important balances must be maintained. Not all nutrients, nitrogen and phosphorous are bad, for example; they must be managed, however, to reach an optimum balance.

Technology is also a factor. If a subject can’t be measured far and wide and inexpensively then causal relationships cannot be substantiated and used in arguments for conservation policies. According to Fisk, relevant new technological developments will play an important role in showing the way to a river full of life.

Habitat and ecology issues also surface, with conservation advocates taking different positions on the same object in different regions. For example, the parasitic sea lampreys are viewed as undesirable in certain regions, but desirable in others, with both directions based on sound eco-logic. In Connecticut, for example, the state is aiding and abetting the growth of the lamprey population by stocking them upriver, and by providing access to their spawning sites above dams. As noted on the Connecticut River Conservancy website, “adult lampreys are an important source of nutrients for our rivers. After they’re born here in the Connecticut River, they head out into the oceans to live and grow. Once full grown, they migrate back to our rivers to spawn. After they lay their eggs, they all die. Their bodies become a food source for all sorts of other river life including aquatic insects, fish, and mammals. Lampreys support a vast food chain that keeps our rivers healthy and full of life.”

One gets the impression that the road to a clean and healthy River full of life will rely more upon persuasion than upon coercion. Andy Fisk seems primed for the task.

Prior to joining the Connecticut River Conservancy as Executive Director in 2011, Dr. Fisk served as Director of the Land and Water Quality Bureau at the Maine Department of Environmental Protection for seven years. As Maine’s land and water quality director, Fisk had extensive experience with a range of state and federal environmental quality statutes.

Dr. Fisk has a Ph.D. in Environmental Sciences, as well as a master’s degree in City and Regional Planning from Rutgers University. He has served as President of the Association of State and Interstate Water Pollution Control Agencies and Chair of the New England Interstate Water Pollution Control Commission (NEIWPCC). He has been active in land conservation for over a decade. At NEIWPCC, Fisk initiated the country’s first regional mercury clean-up plan for the seven Northeast states’ impaired waters, which maps out strategies to make the region’s fish safe to eat. Dr. Fisk is a member of Estuary magazine’s editorial advisory board.