Ferries of the River

By Wick Griswold

Images courtesy of Connecticut River Museum

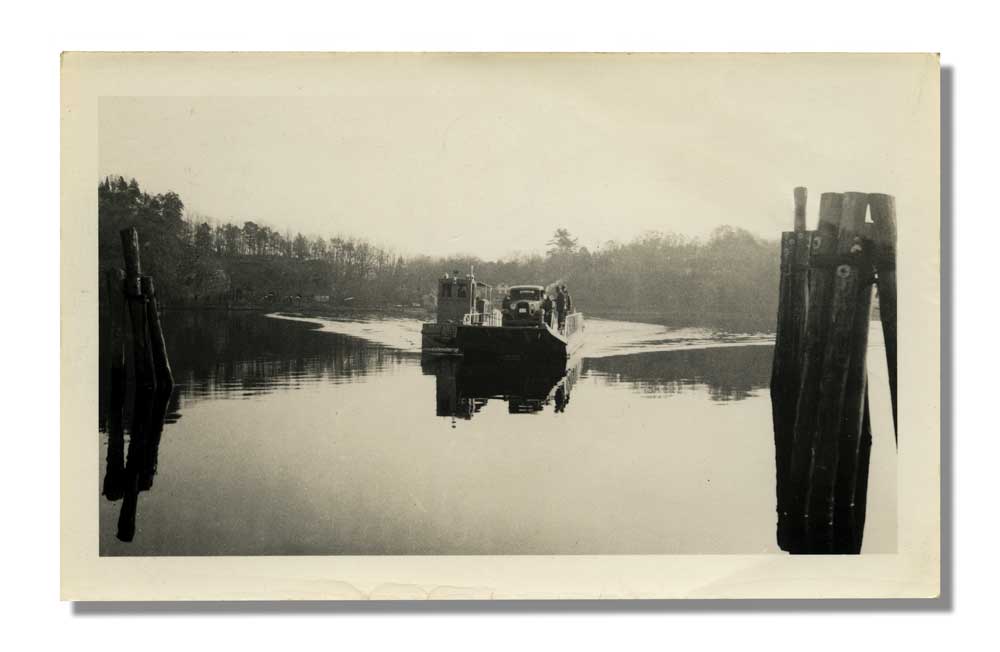

Hadlyme Chester Ferry, Fall 1933, Chester side

The Connecticut River connects us up and downstream. It also separates us from bank to bank. For thousands of years, indigenous people used dugout canoes to get from one shore to the other. The dugout could easily carry the people, meat, plants, tools, and fish around which their foraging lifestyle revolved. Trees transformed into boats were powered by paddle, wind, current, and tide. These organic craft were totally sustainable.

When English settlers arrived in the early 17th century, the canoe quickly became redundant. The colonist’s agricultural way of life required floating platforms to carry draught animals and wagons. Metal woodworking tools allowed the English Puritans to build scows to transport their livestock and gear across the River. These scows were the first ferries on the Connecticut.

When English settlers arrived in the early 17th century, the canoe quickly became redundant. The colonist’s agricultural way of life required floating platforms to carry draught animals and wagons. Metal woodworking tools allowed the English Puritans to build scows to transport their livestock and gear across the River. These scows were the first ferries on the Connecticut.

As early as 1638, the Colony of Connecticut regulated who could operate a ferry, where it was located, and how much ferrymen could charge for people, livestock, and carts. The family fortunate to get a ferry franchise became prominent citizens. They were first to get the news as travelers passed through. Ferryman often built inns and taverns at their slips to enhance their already steady income. Ferry rights were passed from generation to generation.

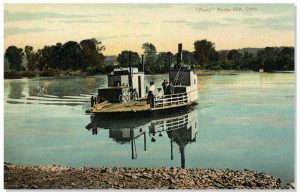

In 1655, a ferry was established between Rocky Hill and Glastonbury. Amazingly, that service continues in operation today! The ferry that connects Chester and Hadlyme came on line in 1769 and still chugs across the River. The original ferryman, Jonathan Warner, gave the operation to his son for a wedding present, with the stipulation that if it earned more than $30 per year the excess profit would revert to dad. Although there were once over 100 ferries on the Connecticut River, these are the only two that remain.

In 1655, a ferry was established between Rocky Hill and Glastonbury. Amazingly, that service continues in operation today! The ferry that connects Chester and Hadlyme came on line in 1769 and still chugs across the River. The original ferryman, Jonathan Warner, gave the operation to his son for a wedding present, with the stipulation that if it earned more than $30 per year the excess profit would revert to dad. Although there were once over 100 ferries on the Connecticut River, these are the only two that remain.

Bridges drove the ferries out of business. The boats were susceptible to ice, freshet, debris, and storms. Early wooden bridges could be swept away or burned. However, stone and steel began to span the River, and ferries were no longer necessary. When a bridge did wash away or burn, ferries were pressed back into temporary service until a new trestle could be cobbled together. Ferrymen fought against bridges in the legislature and town halls, but one by one, the charming boats were retired.

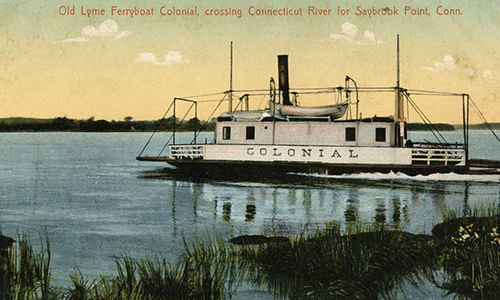

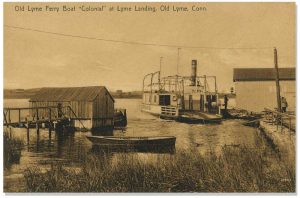

Until the early 19th century, ferries were powered by oars, sails, cables, poles, and horses. Steamboats were invented on the Connecticut River by John Fitch and Samuel Morey. Local ferries were quick to take advantage of this new energy source. Larger steamboats connected River towns to New York, Providence, and Boston. But the new technology could power land-based transportation as well. Soon, railroads were competing with steamers for passenger and freight business. Just as bridges were more reliable than ferries, trains were more dependable than steamboats.

Steamboat lines fought bitter political battles against railroad bridges across the River. They were able to block a train trestle from Old Saybrook to Old Lyme. That bascule, still in operation today, was not completed until 1907. Prior to that time, trains stopped at the River’s edge, uncoupled, slid their cars on to barges which navigated across the River and recoupled on the other side. It was a daunting exercise in engineering and logistics. Today, over 50 Amtrak and Shoreline East trains cross the 113-year-old truss every day.

The oldest continuous ferry service in the US in Rocky Hill-Glastonbury features a doughty, little tugboat, the Cumberland, which pushes the barge Hollister across the River from April to November. The rig can carry three cars, or four, if they are sub-subcompacts. Downstream in Chester-Hadlyme, the double-ended Selden lll can load up to nine cars. The trip affords splendid views of Gillette Castle, and can link with the Essex Steam Train for a nostalgic ride back into railroad history. Both ferries are run by the CT Department of Transportation. Every few years, frugal politicians agitate to end the ferry services. Waste of money, they say. So far, legions of ferry devotees have thwarted their efforts with phone calls, emails, rallies, meetings, torches, and pitchforks.

In June of 2019, the ferries and their fans exhaled a huge sigh of relief. The State of Connecticut allotted $4 million to refurbish the crumbling infrastructure at both landings. Deteriorating pilings will be replaced with wood from South American greenheart trees. It is the most rot-resistant wood in the world. This investment ensures that the ferries will continue to cross the River well into the foreseeable future. Come 2055, 400 years of continuous service between Rocky Hill and Glastonbury will be a commemoration truly worth celebrating.

Renwick (Wick) Griswold is a noted author and Associate Professor of Sociology at the University of Hartford. His signature course is the Sociology of the Connecticut River. He is an associate producer of the documentary Ferry Boats of the Connecticut River. He also hosts Connecticut River Drift on iCRV Radio in Ivoryton, CT, and is Commodore of the Connecticut River Drifting Society.